Daydream Dispatch #3: Claudine Cho

Speechwriter and producer Claudine Cho on grief, community, and storytelling

I heard about Claudine Cho before I met her. Mutual friends urged us to meet, saying we’d get along. They were right. I felt a kinship as soon as we spoke. We got right into it, no room for formalities or insecurities, sharing our fears and desires, what stirred our souls. As you’ll read below, Claudine isn’t afraid to touch the soul; she resides in the house of oof.

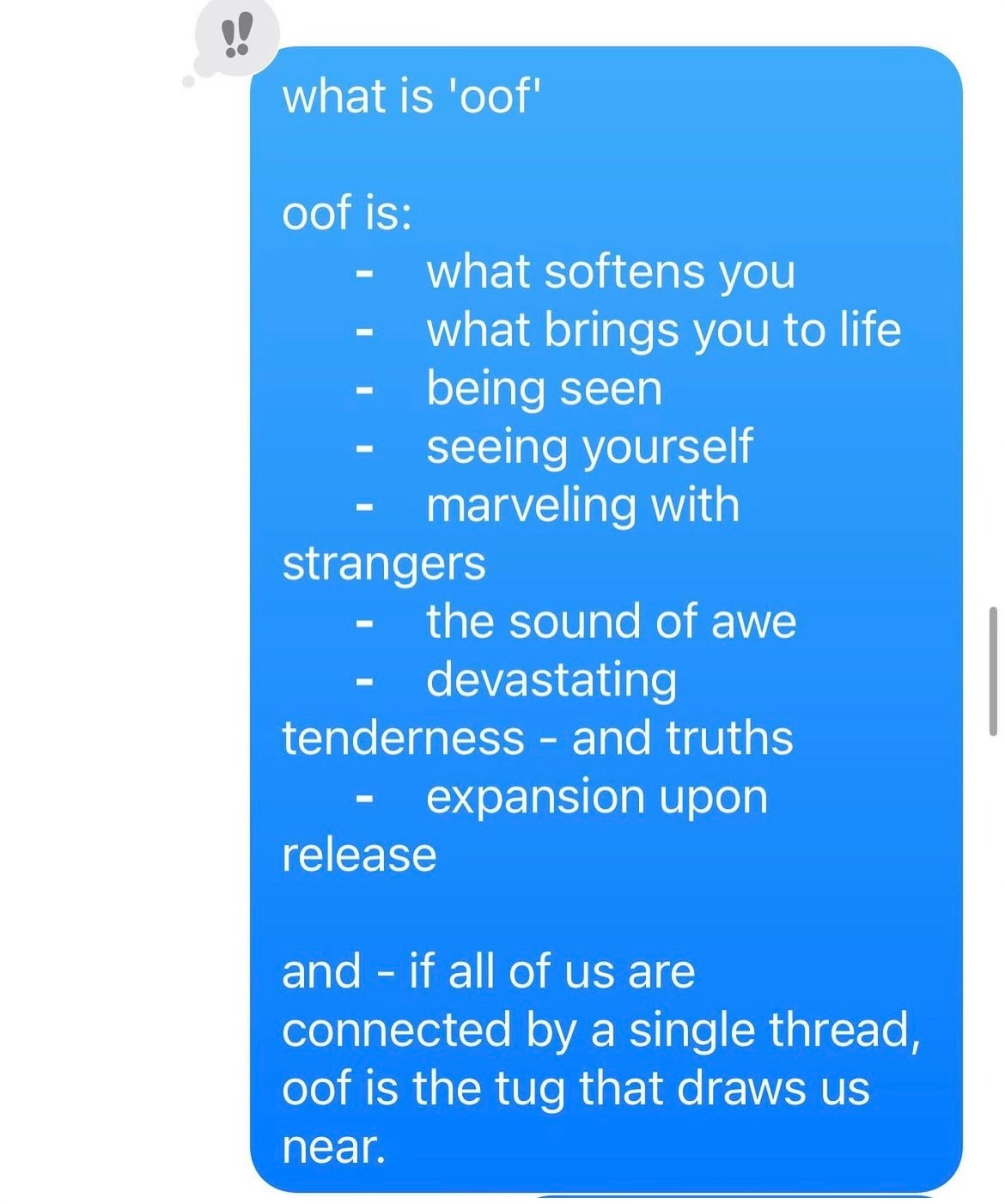

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, oof expresses “discomfort, surprise, or dismay.” Oof is when your heart quivers and the bottom drops out from under you, a moment of free fall that requires surrender.

Here’s another definition of oof, from Durga Chow-Bose’s essay collection Too Much and Not the Mood, which Claudine and I both love:

That spiked measure of awe—of oof—feels like a general slowing, even though what’s really taking place is nothing short of a general quickening. The sheer, ensorcelled panic of feeling moved. Infirmed by what switches me on but also awake and unexpectedly cured.

Claudine and I met at Harvard, an environment that could be stifling. People often postured, taking great care to hide their vulnerability. Claudine did not. The way Claudine moved through the world emboldened me to hold onto my own capacity for tenderness and willingness to be profoundly moved. I talk to Claudine and am reminded that we always have the power to alchemize our grief. It is rare to meet a person who embodies love, and Claudine does. - E

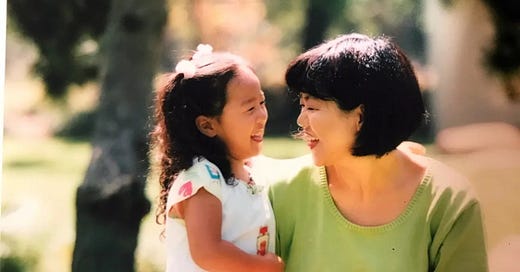

There’s a scene imprinted in my mind, like a flower pressed between the pages of my memories.

My mom in a cherry blossom pink hanbok, receiving a standing ovation at Carnegie Hall. Forty other Korean women—mothers and suburban housewives—surround her on the risers, warmed by the spotlight.

None sing professionally. None have been to Carnegie, except this time to perform. For many their last flight was their first, a one-way from Korea decades ago.

A permanent daydreamer, my mom wanted to be an anchorwoman, a writer, an artist. She fulfilled all her dreams to varying degrees, emceeing church morning services, writing poetry for the newsletter, arranging flowers for community events and the occasional corsage for my highschool dance. And yet, without Carnegie, I’m not certain she would have agreed.

There’s a question I’ve been exploring. Would I still be proud of my life even if none of my dreams came true? Would it have been a good life?

After the show, I rushed to meet my mom at the stage door. She glided towards me on the tails of her gown, her feet never once touching the ground. Mom settled into her newfound radiance well, as if to say this was always her skin.

We all joked, mom could die happy.

Six months later, she did. It turned out that her *snatched* waist wasn’t due to her pre-show regimen, but an aggressive cancer, tearing her body from within.

In her BAFTA speech, Celine Sciama, screenwriter and director of the award-winning Portrait of a Lady on Fire, talks about scenes as units of desire. “The ones you don’t have to look for; they are your compass, the ones you make the film for. Sometimes you don’t even know why, you just know they will be in the film. And you should respect that.”

It feels reckless to pursue filmmaking just to memorialize a scene, but what else do you do when you witness a miracle?

I call it a miracle not because of the hallowed stage, but because 40 Korean women, mothers and suburban housewives, came together to reclaim their lives.

To me a miracle is the tenderness we possess despite the opportunities to harden. The making of any film. To know grief and still dream.

Like many immigrant mothers, my mom’s life was marked by sacrifice. Because of this she frequented the past to sit with the dreams she left behind.

But during what our family refers to as her finale, she lived for herself. Our always-bursting fridge was left forgetfully empty. Mom disappeared on long road trips with her choir friends. She let our calls go to voicemail.

The rest of us faded into the background and I found relief in becoming an afterthought. I was free to live my life, unencumbered by her lifetime of sacrifice, as was she.

I’ve learned that without action, daydreaming can harden into regret. So now, when I find myself unable to shake a dream, I share it with my loved ones.

That’s how OOF stories, the AAPI (Asian American and Pacific Islander) documentary collective I co-founded, came to be.

Three years ago I met a stranger at a summer BBQ. The gay son of pro-reunification activists, he spent his childhood beating protest drums to energize comrades marching for Korea’s liberation.

At the time of OOF’s founding, hate crimes against our AAPI elders and loved ones were at an all-time high, so this image of militant Asians lit a fire in my belly.

Frustrated with the tired narratives the media had prescribed to our community, I thought – What if we invested in our own stories, about what makes us come alive?

That’s led us to:

Alice of Hana Makgeolli, a Korean-American rice wine maker reviving ancestral methodologies to create the first domestic brewery for traditional sool.

Sammy of Lambert Studio, a wedding florist who is at the peak of his career when he decides to retire.

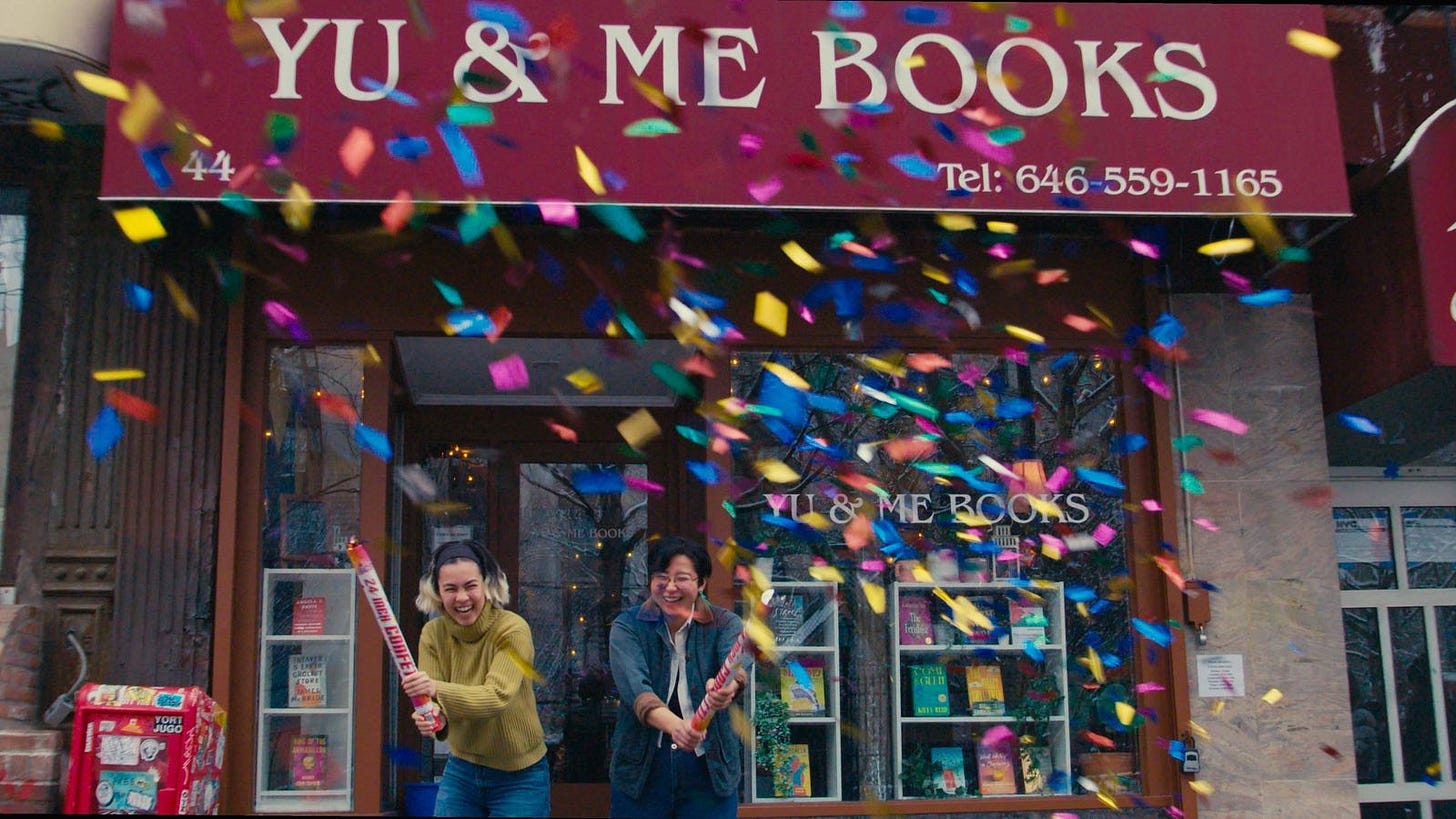

And Lucy of Yu and Me Books, New York’s first bookstore run by an Asian woman. After a fire devastates the store, thousands of supporters and friends come together to help Lucy rebuild the beloved community bookstore.

I often wonder what it means to live a good life. For the first time, it feels nothing more or less than my life now. I’m grateful for my softness, to be quick to tears, to marvel and create, to know love and to expect it, and to share this life with my loved ones.

I’m even grateful to know grief, because every time I’m moved by the beauty of this world I think about my mom. And then I’m reminded that grief is a gift of love left behind.