Where was I when I first heard “Dreams”? I must have heard it dozens—if not hundreds—of times on the radio, in fast-food chains and malls. But it never registered.

What made me hear it differently? Where was I? In my bedroom of course, the blinds shut, headphones on. I’m somewhere between thirteen and fifteen. I hate everything about myself and I’m greedy to get out. Out of my body, out of my mind, out of this suburban town I’m starting to hate. It becomes a litany I repeat to myself each night, the first promise I ever make to myself and keep: you will leave this place and never look back.

I’m restless with my new need. Thank God there is the Internet, and Tumblr, because I can go so many places without ever leaving my room. I learn about bell hooks and post-dubstep and David Lynch this way. I scroll and scroll but it doesn’t give me the hollowed out feeling Instagram will a decade letter. Doom scrolling. Did it even exist then?

I’m greedy for information. It is my parachute, my life raft. My mind swells with it, the excitement of taking new things in, deciding what I like and don’t like. Developing that mysterious thing called taste.

It’s a song I will have to discover on my own. My parents know nothing of Fleetwood Mac. The closest type of music we have in the house is The Essential Bob Dylan, which my dad loves.

Sometimes I think I know the opening bassline to “Dreams” better than any other song. A clarion call I feel deep in my body right as it starts.

What was it about that first line? What caught my attention? Surely it was Stevie’s voice; a sound not exactly pretty but not ugly either. A little nasally, sure. But it undeniably had character. From her voice spoke another voice, ancient and all-knowing:

Now there you go again you say you want your freedom. Well who am I to keep you down?

She sounded so wise, even a little above it all. But then there’s the next line, the one that made me sit up a little, that gave me goosebumps:

It’s only right that you should play the way you feel it

It wasn’t necessarily the lyrics but the way Stevie’s voice curled around them. It’s only right she says but you know that it isn’t.

“Dreams” is a song about loneliness that somehow never makes me feel lonely, although in listening I certainly get close to the feeling. It’s bittersweet through and through.

Fleetwood Mac recorded “Dreams” at the Record Plant in Sausalito. Sly Stone had a studio there, which everyone jokingly referred to as “The Pit.” One afternoon, sitting in Sly’s fabulous “big black curtained bed,” Stevie wrote “Dreams.” She knew right away that it was special. “I was not self-conscious or insecure about showing it to the rest of the band. I knew they were really going to really like it.”

Rumours, the album Fleetwood Mac would go on to create at the Record Plant, immediately topped the charts upon release. But it was created during a period of immense strife within the band. Stevie and lead guitarist Lindsey Buckingham’s relationship had fallen apart, as had the marriage of fellow bandmates John and Christine McVie. (Things got increasingly tense after Christine started an affair with the band’s lighting director Curry Grant.) But everyone pushed through, keeping it together for the sake of the album. Some of the album’s best songs—“Dreams,” “Go Your Own Way,” and “Never Going Back Again”—are about breakups that happened between bandmates. Stevie, of course, wrote “Dreams” about Lindsey.

It’s September. I’m newly twenty-one and full of possibility. I’ve moved from the center of campus into a house. It’s big and has a walk-in freezer where we store cases of produce I learn to cook for the first time: fennel, Brussels sprouts, leeks. A porch, too. My room is on the first floor; my bed is pressed up close enough to the window that I can hear each creaky footstep.

We throw a party, partly in celebration of our cleaning but also because it’s someone’s birthday and we must celebrate. It’s the end of the party now but I’m still dancing, something I unabashedly, to this day, love to do.

Someone’s talking in the backyard. Someone’s making bread, having a cigarette, revealing a new crush.

When the song changes I know instantly what it is. There it is, floating out to me from the inky night. I’m giddy with my love for the song and how it crystallizes everything I’m feeling. I spin and see my reflection in the windowpanes.

In my journal that week I write:

I’m not sure if there can be a single truth to a person, or a set of experiences, but there is this fundamental gap…

When I hear “Dreams” now—not as often as you’d think—it’s often in passing. Blasting from the car next to me or a boutique I pass by. I always consider it a good luck charm, like the quick sight of a hummingbird or monarch. I’m still here, all these years later, and Stevie’s still got me.

If I’m honest, I’ve been struggling to dream these days. I’ve been struggling to make sense of the larger world and my place in it. I know human life and history has never been void of violence and cruelty but it feels especially salient these days. I’m struggling to find clarity, a way of speaking about “our time” that isn’t clichéd. Language often fails. One morning I found myself returning to Judith Butler’s essay “Violence, Mourning, Politics” in Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Justice. Butler writes:

Is there something to be gained from grieving, from tarrying with grief, from remaining exposed to its unbearability and not endeavoring to seek a resolution for grief through violence? Is there something to be gained in the political domain by maintaining grief as part of the framework within which we think our international ties? If we stay with the sense of loss, are we left feeling only passive and powerless, as some might fear? Or are we, rather, returned to a sense of human vulnerability, to our collective responsibility for the physical lives of one another? […] To foreclose that vulnerability, to banish it, to make ourselves secure at the expense of every other human consideration is to eradicate one of the most important resources from which we must take our bearings and find our way.

To grieve, and to make grief itself into a resource for politics, is not to be resigned to inaction, but it may be understood as the slow process by which we develop a point of identification with suffering itself.

I’ve always been moved by the way Butler formulates our relationship to one another as human beings. I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t aware of my vulnerability as a body subject to other bodies. It’s frightening but inescapable.

In “The Work of the Witness,” Sarah Aziza asks “What does all of this looking do?” as the world watches Palestinians die by the thousands:

Watch, I tell myself. I see what must have been a building, though all that remains is a smoking hill of sharp debris. Watch, I tell myself, as thin men in sandaled feet rush into the frame. They begin pawing at the slabs of cement, rebar, brick. Shouts ricochet. The camera moves closer. My ears begin to ring. I long to click away. Watch. These are your people. I force my eyes to stay.

These are your people. A sentiment I’ve felt when hearing news from Haiti. It’s never good news. I worry what other people think of my people, to see them driven to such extreme violence. I don’t know when or if I will ever be able to return. I may never see where my mother and father grew up. That, too, is a form of grief.

Aziza grapples with what it means to bear witness. There’s the pressure to share photographs of her family members. “Our bodies are so precious,” she insists. “If we never saw another photograph, our purpose would still be clear. This week’s photographed corpses should have been saved by last week’s ceasefire; the same will be said every week until this evil ends.”

What will we do with our looking?

This week’s recommendations and encounters:

I. A book

I’ve been thinking about the future. I know I’m late to the party, but speculative fiction—especially fiction about dystopias—has increasingly felt like a generative space to think about possibility. I’ve always been a little afraid of sci-fi, but reading Ursula K. Le Guin and Octavia Butler for the first time last year changed that for good.

I read The Emissary by Yoko Tawada last week. It’s a bittersweet and refreshingly original novel about a post-apocalyptic Japan in which the elderly live forever and the young are feeble. Despite the potentially dour subject matter, the writing is buoyant and playful. I hadn’t encountered that kind of tone in a work of speculative fiction before and it really resonated with me.

II. Two interviews

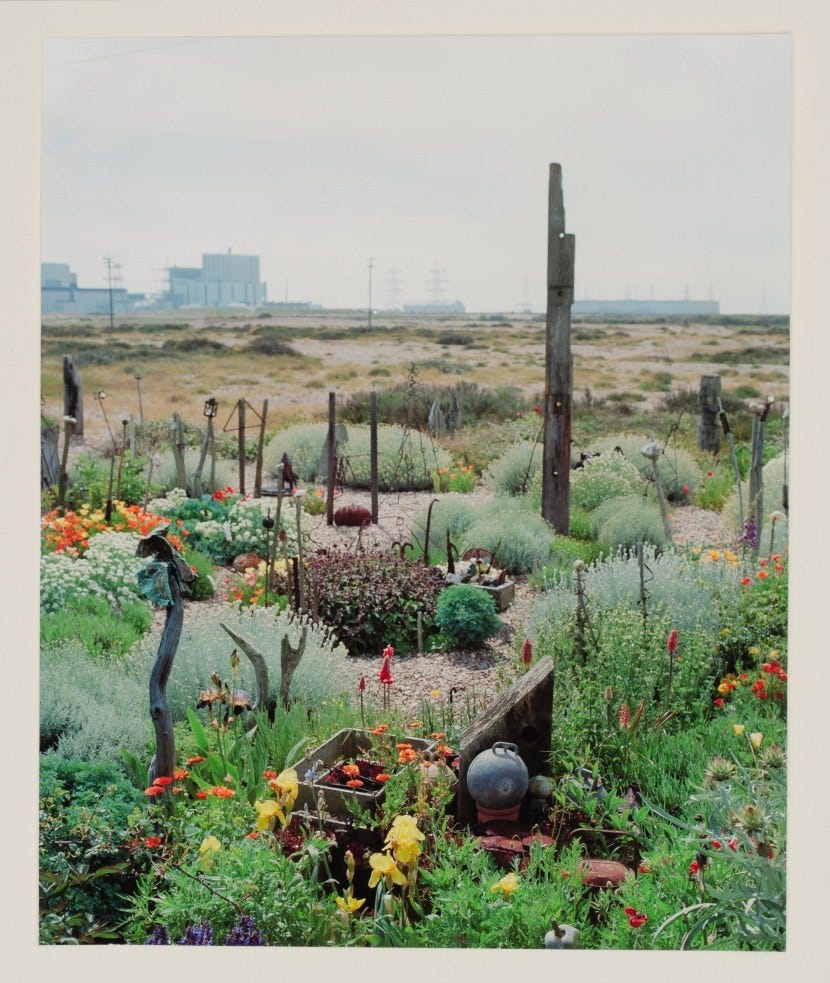

I had the honor of interviewing Olivia Laing and Maggie Nelson about their newest books. As a gardener it’s no surprise that I loved Laing’s book, The Garden Against Time: In Search of a Common Paradise. I’m always going on about the garden as this magical space of possibility yet I often feel silly doing so; Laing sheds light on how gardens have functioned as a refuge for “rebel outposts and dreams of a communal paradise.”

One character Laing returns to throughout The Garden Against Time is the artist and filmmaker Derek Jarman. Laing’s deep interest in him and his work sparked my own curiosity. I plan to start with his film Blue and the journal about the garden he started on Dungeness coast, Modern Nature.

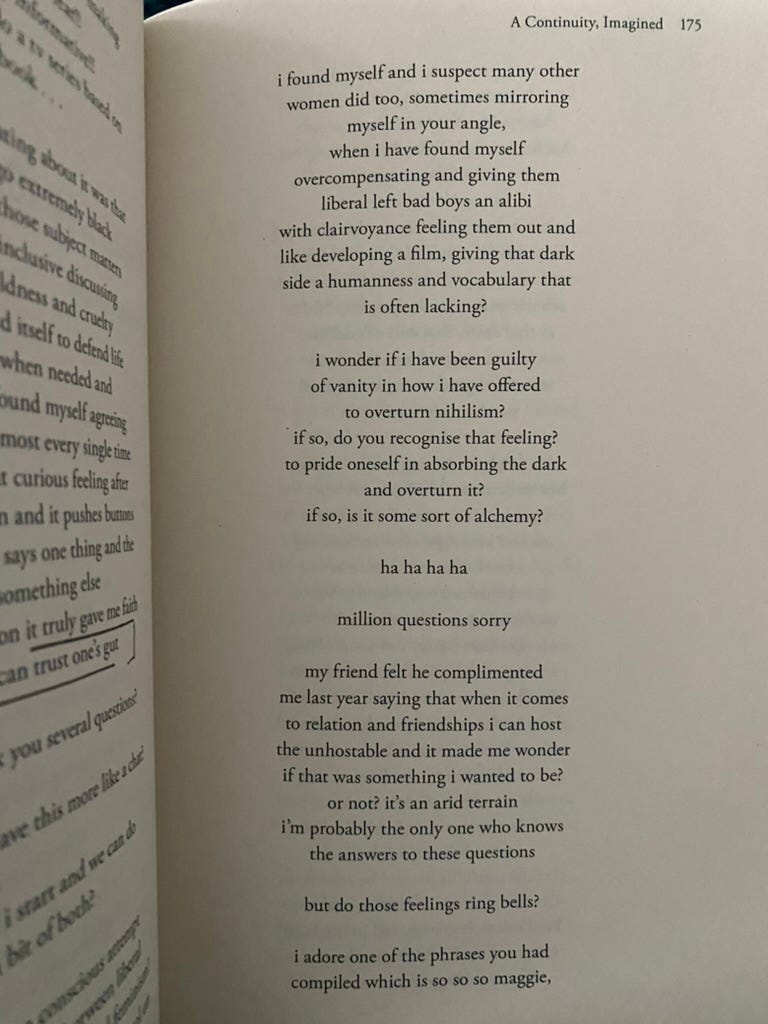

If you’re a fan of Maggie Nelson’s writing (and brain like I am) Like Love is essential reading! It’s a collection of Nelson’s shorter writings and features conversations with Björk and Eileen Myles.

I re-read Nelson’s work in preparation for my interview with her, which only deepened my appreciation of her writing. It’s always a pleasure to think through things with Nelson and watch her mind work on the page; she makes criticism feel pleasurable, exciting, invigorating, and a necessary part of being alive.

III. A few exhibitions

Simone Leigh opens at LACMA this afternoon. Leigh represented the United States in the 2022 Venice Biennale; I’ve been dying to see her work ever since. I’ve been eagerly awaiting the opening for months, and I’m certain it’s a show I’ll return to again and again. Thankfully, it’s on view until January of next year! Leigh’s work will also be on view at the California African American Museum, which just re-opened.

Other exhibitions I’m looking forward to seeing this summer: Mickalene Thomas: All About Love at The Broad, on view until September 29, and Keith Haring: Radiant Vision at the Long Beach Museum of Art, on view until August 25.

As always, thank you for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please don’t hesitate to subscribe or, better yet, share it with someone!

I’ll see you in a few 💌