What do you pay attention to? It’s a simple question but one that can determine the course of our lives, or at the very least, our days.

It’s a question I started to ask myself after I noticed how much time I was spending online, particularly Instagram, and why I would feel so badly afterwards.

It was like falling into a void of time. I hated how this made me feel. It was a new habit and it was coinciding with an unhappy period in my life. I got lost in the lives of others, pulled into their days through Stories. I started to grow resentful and ungrateful, ignorant to the beauty in my own life. I suffered because the present was starting to feel unbearable. I always wished to be elsewhere.

My relationship to Instagram and the internet in general has changed a lot since then. I’m still frustrated by it—how it co-opts our energy, attention, and time, how it flattens discourse. It’s definitely making us all lonelier. But it’s helped to see social media and the internet at large as just a tool, something I can use in a way that is specific and particular to me. Through the internet, we now have more access and information than ever before, from data to ideas to people. It’s truly dizzying. But is all that extra information actually making our lives better?

I wrote about this a bit in last week’s supplemental post, but in 2022 I found myself ruminating on the role beauty and attention played in my life. It was a throughline in the works of art I found myself drawn to and referenced by authors I admired deeply—Zadie Smith, Maggie Nelson, and Sigrid Nunez, to name a few.

Two names came up time and time again as I read, Simone Weil and Elaine Scarry. The title of Sigrid Nunez’s 2020 novel What Are You Going Through? is from a line in Simone Weil’s essay “Reflections on the Right Use of School Studies with a View to the Love of God.”

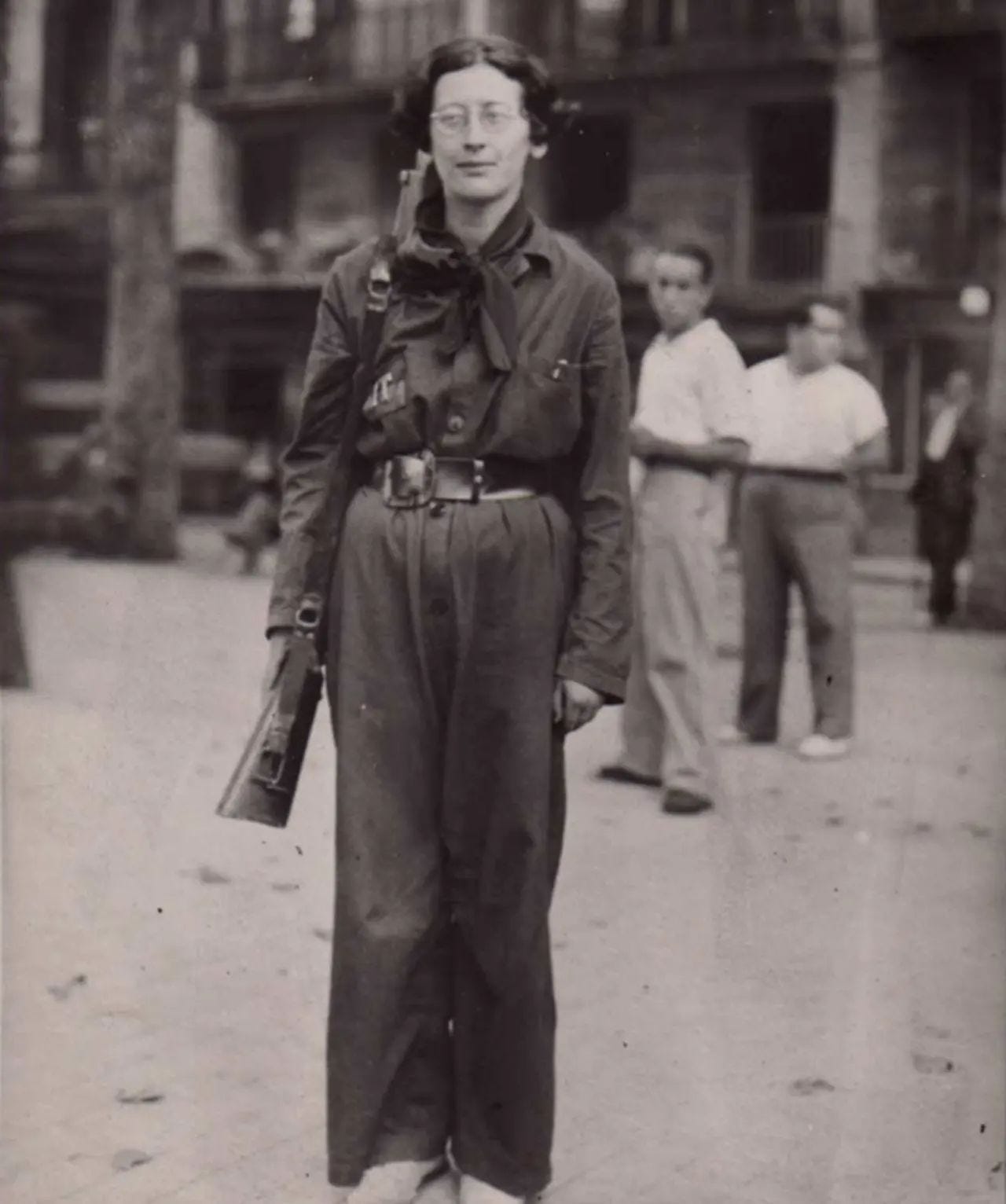

Weil was a French philosopher, activist, and mystic who fought in the French Resistance. Her life’s work was short but intensely fruitful; she died at the age of 34 but wrote and published an astonishing collection of essays. Weil arrived at her philosophy through her involvement in the trade union and Spanish anarchist movements. Working in a factory changed Weil’s understanding and experience of suffering, particularly the suffering of others. In Waiting for God, Weil writes, “The capacity to give one’s attention to a sufferer is a very rare and difficult thing; it is almost a miracle; it is a miracle. Nearly all those who think they have this capacity do not possess it.” For Weil, true attention comes from a sense of waiting and involves a negation of the self. She writes of it as a “faculty that does not latch onto the other, but remains still and open.” It’s a description that brings to mind the aperture of a camera, still and ready and waiting.

I’ve slowly been making my way through Weil’s essays. Alongside Weil’s work, I highly recommend reading Robert Zaretsky’s biography of Weil, The Subversive Simone Weil: A Life in Five Ideas. Once I started reading Weil and about her, I found myself fascinated by the intensity of her devotion. (In another life I think I was a nun or mystic because I often fantasize about living a life devoted to the act of contemplation.) She truly lived according to her political and ethical ideas. Her moral philosophy always had a social dimension, one that depended on one’s capacity for attention and, importantly, care. It was a morality that extended outwards and didn’t involve you. You became diminished in the face of what was in front of you, what you were forced to pay attention to.

I was particularly struck by the notion in Weil’s work that suffering, justice, and beauty are all related. “In the true portrayal of affliction, what creates beauty is the light of justice in the attention of the man who portrays it; this attention becomes contagious through beauty,” Weil writes.

I say this (sort-of) jokingly, but we live in a Godless time. I’m not religious so I don’t mean this literally. But the increasing rarity of third spaces and general loss of community in our society throughout the last few decades makes it harder and harder to come by moments of grace in our daily lives. We shuttle from work to home and then into the world that is the Internet, unable or unwilling or just too damn exhausted to step outside the bubble that can so easily become our life. Soon enough, the edges of our days start to harden. We grow defensive and closed off to the world, our capacity for true attention diminished.

I’m particularly biased, of course, because I live in Los Angeles, a city that famously induces feelings of loneliness. It’s a city known for its beauty, found in both the landscape and its people. But I’ve found it to be a beauty that can be alienating or difficult to access. And often it literally is; in Los Angeles, the amount of greenery in a neighborhood tells you about its milieu. Like many cities in the United States, driving throughout LA reveals a narrative of exclusion, discrimination, and gentrification. I live in Hollywood at the base of the hills, so I sometimes feel moored in a land of extremes. Immense privilege exists literally above me in the form of multi-million dollar homes, the encampments of the houseless just a few blocks down below. Who has access to beauty? I find myself asking. What role does it play in our lives? What are its political dimensions?

Attention also has to do with taste; what we decide to pay attention to reveals our values. Those values can be expressed in what we listen to and watch or what we decide to spend our money on. Taste, like attention, also has a moral capacity. In making a statement about your taste, you reveal what is meaningful to you.

I thought about all this while listening to “How to Discover Your Own Taste,” a conversation between host Ezra Klein and author Kyle Chayka on Chayka’s forthcoming book Filterworld: How Algorithims Flattened Culture. Klein opens with this idea of the Internet “not being fun anymore,” a thought I’ve had myself recently. I found myself missing the heyday of Tumblr, where I discovered some of the artists and works that became foundational for me: Jenny Holzer’s Truisms series, Maggie Nelson’s Bluets, and Julie Dash’s legendary 1991 film Daughters of the Dust. That version of the Internet was less algorithmically-driven and therefore felt more personal.

It felt like an exciting time, more exciting than now. I’ve often wondered if my nostalgia for it is just a product of getting older. But listening to Klein and Chayka’s conversation made me wonder if 2013/2014 was a golden period after all. In the introduction, Klein says:

We moved, at some point, from this period where the internet was about curation. It was about finding these individuals who would welcome you into these worlds they had created and found and put together for you, to this internet of algorithms. One of the quiet things that happened […] is that it became harder to feel like you were finding individual experiences on the internet, and it became harder to be an individual on the internet. And because we live a lot of our lives on the internet, that means it also became harder to be an individual.

And as this yearning for this digital life that I feel like I once had, and no longer do, has grown, I’ve noticed myself in my own life seeking out people who are individuals and people, more than that, who seem to have their own sense of aesthetics of style, of taste.

These weren’t things that were that important to me a decade ago. But they’ve become more important to me now. I’ve come to see them almost as a kind of superpower, both because just living a beautiful life or living a life in which beauty has a central role feels more important to me as I get older, but also because it feels increasingly like a kind of superpower, like a kind of act of resistance against what these algorithms and what this age online is doing to us.

It feels like being able to be attuned enough inside yourself to know what you really like, not just what you’re being fed, being attentive enough to the world around you to see things that are really yours, not just everybody else’s — it feels like an important way to live.

I was struck by Klein’s formulation of taste, particularly how he relates it to the concepts of attunement and attention. I love the idea of using attunement as a verb, thinking of it as a process of calibrating one’s attention.

This week’s encounters:

I. Some rules for making (and living):

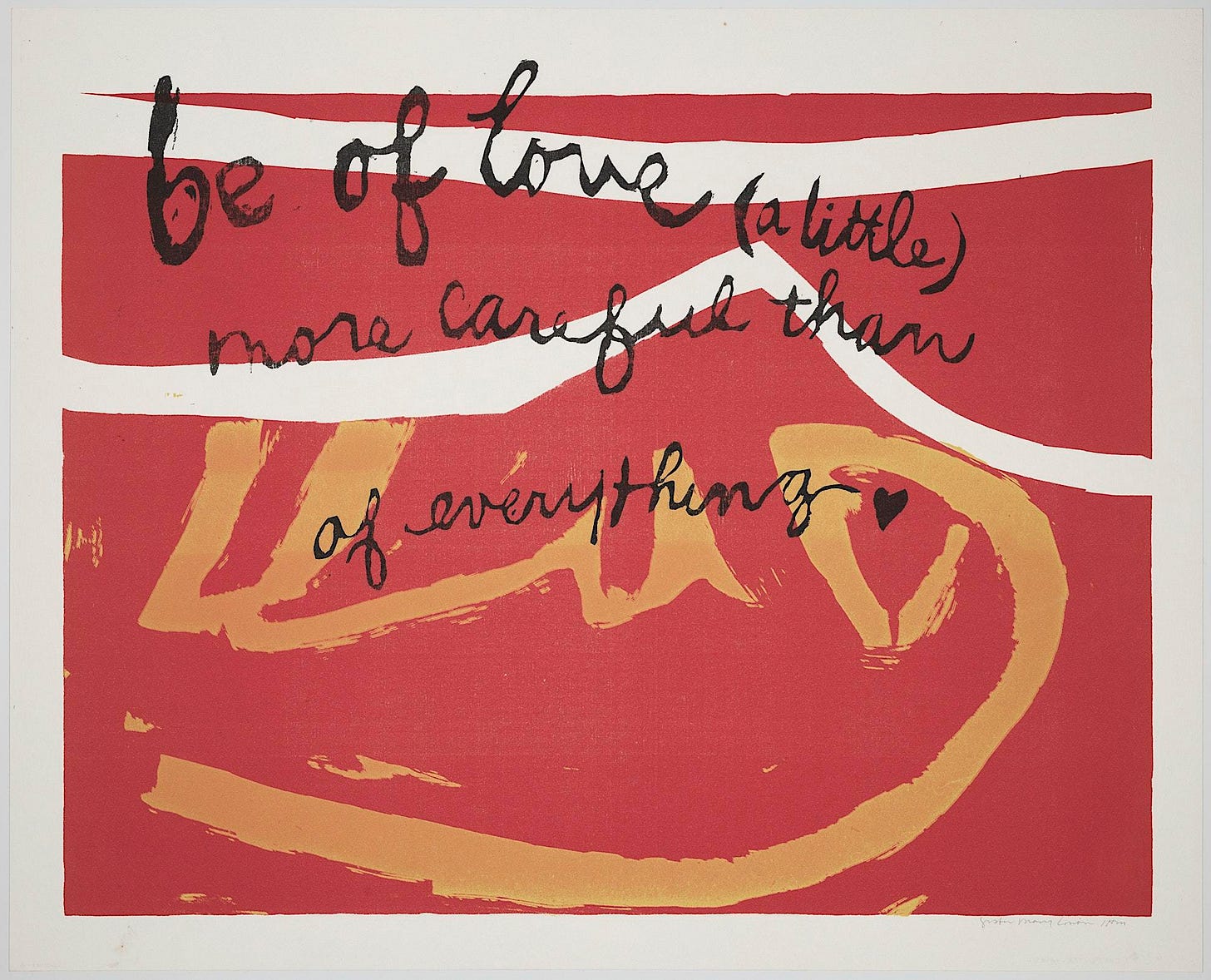

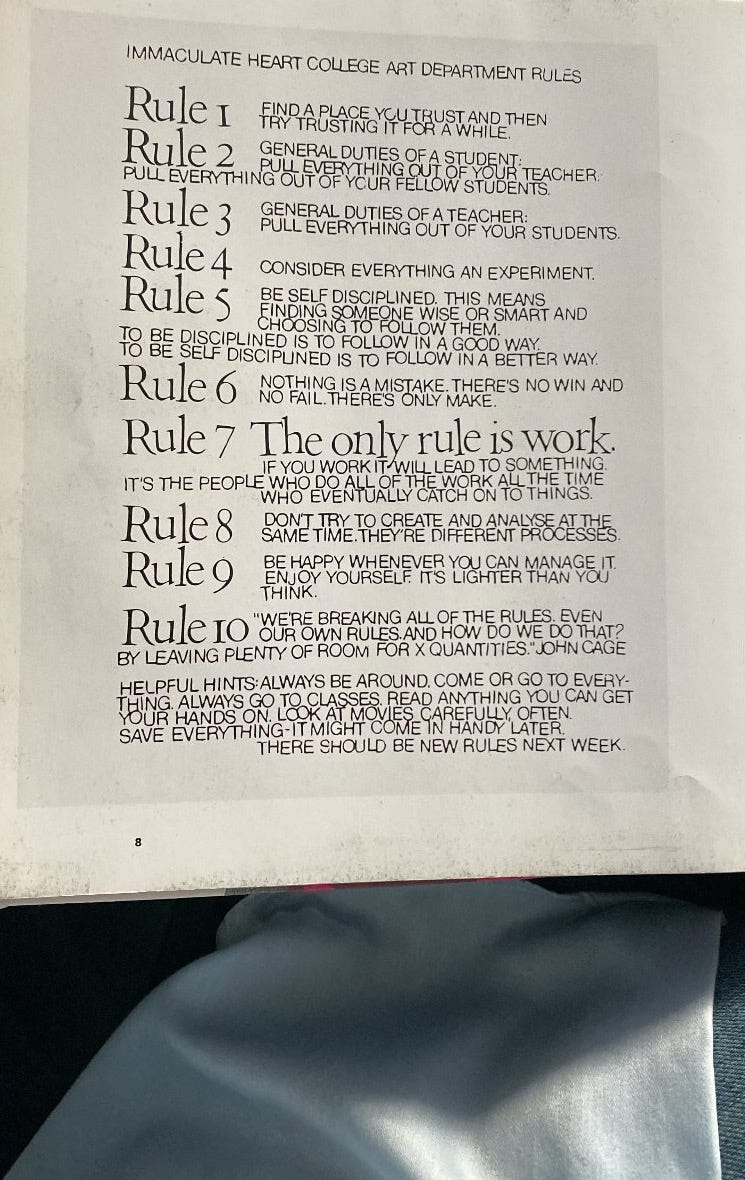

This week, I started reading Someday is Now: The Art of Corita Kent. My coworker E first introduced me to her work through Ordinary Things Will Be Signs for Us, a collection of Kent’s photographs. Corita Kent, also known as Sister Mary Corita, was an artist, educator, and advocate for social justice who headed the art department at Immaculate Heart College. Above are Kent’s “10 Rules for Students, Teachers, and Life.” A list I’m taking to heart.

II. An exhibition

If you happen to be in New York until February 10th, you can see Books: A Group Exhibition at Paula Cooper Gallery. Like the title suggests, it’s a show entirely dedicated to the subject of the book, and includes work by Theaster Gates, Sophie Calle, and Ed Ruscha. “The gathering of works will demonstrate the many ways in which contemporary artists have engaged with the book as surface, structure, found object, and philosophical guide.” A dream exhibition!

III. A series of photos

I came across these photographs of East LA’s Chicano residents via MOCA’s Instagram, which were shot by John Valdez in the 70s. I love the confidence and personality projected through each person’s sartorial choices. To me, the act of getting dressed can be another form of beauty, one that has nothing to do with fashion trends or luxury brands. I think the best style is personal, romantic, and even a little nostalgic; it’s about the textures and colors you feel good in and bring you back to yourself. That can be through an expensive bag or a pair of $20 vintage jeans that make you feel comfortable. It’s about finding what allows you to carry yourself with grace. Like anything in life, it’s not the what, but the how.

As always, thank you for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please don’t hesitate to share it. These weekly posts are free, and every single view and subscription directly supports me and my work.

If you’re interested in keeping up with my other writing, you can follow me on Instagram. This week I covered AFROSPORT, a fantastic survey of African sports through the lens of design, for Another Magazine. Until very recently I haven’t been that interested in sports, but reading the book enriched my understanding of it. It'll sound obvious to, well, pretty much everyone who isn't me, but it's been fascinating to consider how sports touches everything: politics, fashion, art…

I’ll see you in a week 💌