I notoriously have an awful memory. I always have, ever since I was a child. My mother would bring up some person—usually a family member I definitely ought to have remembered—and my mind would go blank. I once watched a documentary with her about a man who could recall his memories—down to the date and time—with perfect accuracy. I was shocked; there were people whose brains worked like that? If my brain were a desktop, my memories would be scattered folders with partially named files, date and origin unknown.

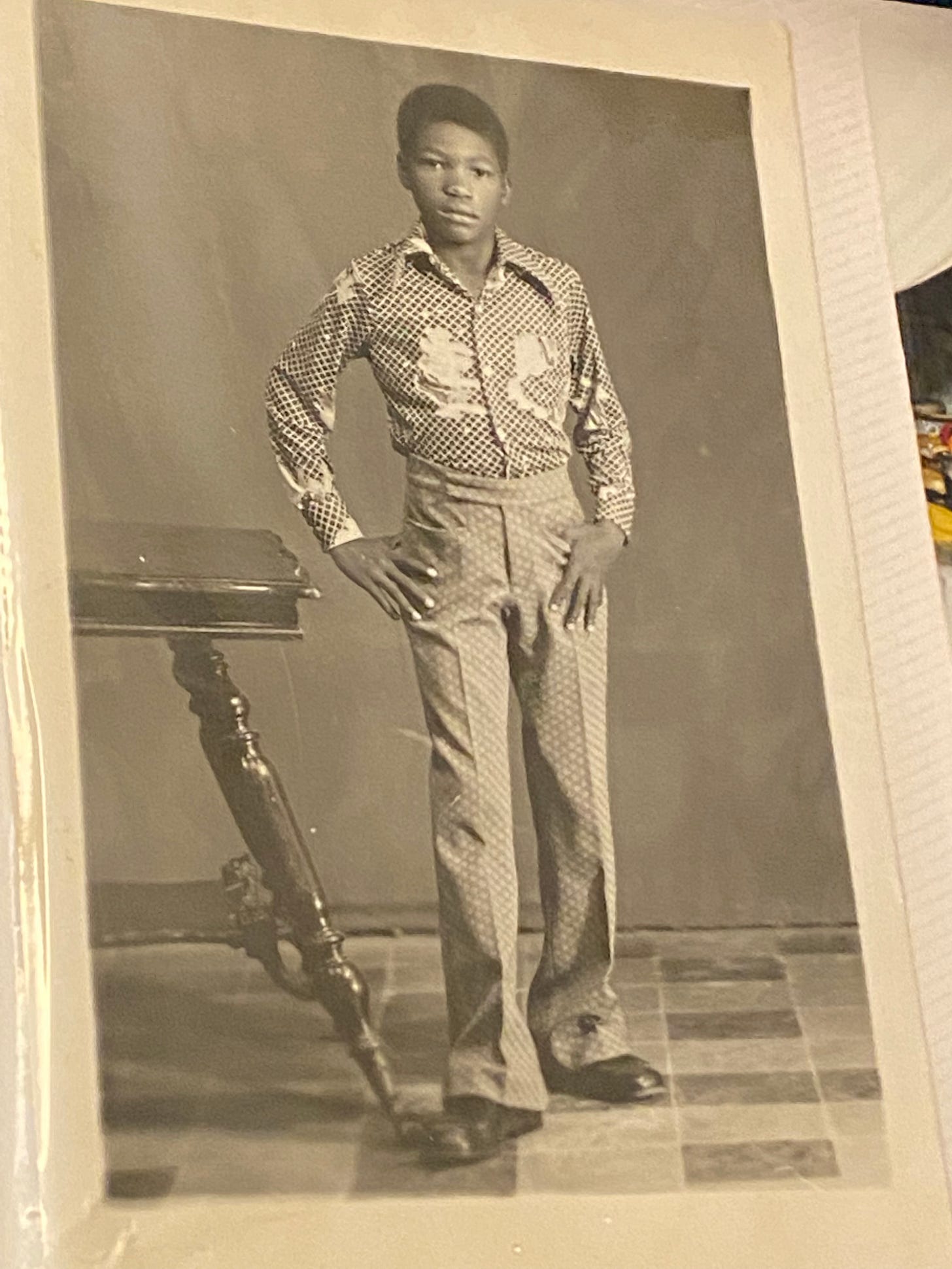

Growing up, I latched onto the stories about Haiti my parents narrated to me. I can’t remember when exactly the tradition started—maybe it was less of a tradition, but a question I would ask over and over again—but on my birthday my father would tell me a story about what he was like when he was my age. In my mind’s eye these stories have the resonance of pictures. I can still see how I first imagined my father as a child, a strange amalgamation of the man in front of me and the photographs I’d pull out from time to time. These photographs—yellowed studio portraits and faded landscape scenes—were my only glimpses of Haiti.

My parents’ home country felt like a missing puzzle piece, a clue to understanding the enigma that they were. Haiti. It soon took on a mythical quality. Unlike some of my cousins, we never went back to visit, although my father would eventually travel back and forth from there to the United States for work. Despite growing up seeing my likeness reflected in the Haitian art that hung on the walls of my childhood home, I felt completely isolated in my culture and heritage. Although I couldn’t have articulated it at the time, I craved a sense of what I can only describe as landedness in my body. (A vital memory: arriving at the airport in Port-au-Prince for the first time, looking around at the people who, inexplicably, all seemed to look like me, and thinking, oh, these are my people.)

When it came to Haiti, there was always a sense of precarity. It is a country whose history has been plagued by tragedy, to a Shakespearean degree. (Haitian history often reads like a tragicomedy.) Things in Haiti—people—could disappear. They often did. The 2010 earthquake was my first memory of seeing my people represented publicly in a visible way. Yet that visibility was centered around poverty and despair. Yes, it was reality. But not the entire picture.

As I write, Haiti is going through a terrible crisis. As the child of immigrants, I already feel a sense of diasporic loss, but even more so when I see what my people are doing to each other. I’ve always felt a strong sense of pride in being Haitian; we led the only successful slave revolt in history, after all! When my father left the country for the last time, he made sure to take works of art with him. I think about those artists, the ones who never had a chance to begin with, and the legacies they’ll likely never leave behind. These omissions in the archive leap out at me, bringing about a kind of grief.

Maybe it’s precarity that shapes my relationship to memory, and therefore to loss. The gaps in my childhood memory feel most salient when I think about the blank spaces that appear in my mind when I try to recall my grandfather, and my grandmother, too. I don’t ever recall meeting my father’s father, even though my father tells me I did. I was two. We were in Brooklyn. I wonder about these people who made my father. The man who spent 3 1/2 years in prison, who likely feared the fall of the machetes and the heavy boots of the tonton macoute, the army sent to do Papa Doc’s bidding.

How did he survive, I wonder? And how did she, my grandmother, with children to feed and take care of. What kept them alive?

I’ve always been fascinated by the role memory plays in the creation of art. Artists often use memory to create their works, but the creation of art shapes memory, too, especially memory that is collective. When it comes to nation-building, monuments are often used to construct a particular narrative. Often these narratives are centered around what it means to be a citizen, or a collective understanding of some historical figure or event.

I recently encountered the work of Israeli curator Rona Sela. Since 1996, much of her work as a researcher and curator has been about using archival practices to examine the way “Israeli national/colonial archives have become a large reservoir of knowledge and information about the Palestinians” and Israel’s “control over knowledge and the writing of history.” In an effort to counter this systematic control and erasure, Sela has published books on Palestinian photography and curated exhibitions on Zionist propaganda and photography, the vast collection of images of Palestinians held within Israel’s military archives, and more. She writes:

The Zionist leadership believed that in order to establish its control over a conflict-ridden country and gain the support of international public opinion for the establishment of an independent Jewish state, it must, inter alia, establish an unequivocal self-promotion system. It used the infrastructure created by 19th century European photography as marketed in the western world, employing its perception of the Holy Land as biblical and as linked to the New Testament - a land where very little has changed (destitute and underdeveloped), as well as its attitude toward the “Oriental Other” (as backward, yet symbolizing biblical figures). European photography ‘delivered the goods’: an exotic, magical biblical-primitive Orient.

The Zionist establishment used these colonial images, and others, for its own needs, and through the “undeveloped Other” shaped the “modern” identity of the New Jew in his land. The juxtaposition of sparse underdeveloped settlement and a vast settlement enterprise with distinct modern, western features, as well as the representation of a ruined, neglected, barren land waiting to be reclaimed – all these provided political power, especially since the bodies that were to decide on the question of the conflict between the two peoples were western. Furthermore, the use of the biblical image embodied a response to the question of historical right over the land.

In 2017, Sela directed and wrote Looted and Hidden - Palestinian Archives in Israel, a film centered around “the Palestinian archives that were looted or seized by Israel or Jewish forces during the 20th century and are controlled and buried in Israeli military archives.” You can watch the film here. I recommend The Palestinian Museum Digital Archive, too.

In Driving in Palestine, artist Rehab Nazzal documents “the architecture of occupation” present throughout Palestine. “The images flowing across Driving in Palestine don’t present cruelty in the same sense as those that witness a moment of death,” writes Canadian filmmaker Christina Battle on Nazzal’s photographs. “They don’t document that particular gory reality, shaped by brutality. Their focus is on the infrastructure that makes cruelty possible, inevitable, visible. These images contain within them the traces of events left unseen by those at a distance.”

Traces of events left unseen.

Lately, I’ve found myself reflecting on the role the archive (and art) plays in the preservation of memory and life. More than 30,000 Palestinians have been killed since October 7th. Many of them were poets, writers, and artists. Dreamers. What happens to the work they produced? How can their work be cherished and kept alive? How do we hold onto what is being lost?

Photographer Adam Rouhana is part of a generation of Palestinian photographers who have been, in his own words, creating “a contemporary Palestinian visual language, inscribed with an ethic of self-determination” to stand against “forces of erasure.” In an essay about his photographic practice for The New York Times, Rouhana writes:

When I picked up a camera at age 12, I began taking photos of what was around me: Palestinian life.

As I got older and developed my practice, I noticed a dissonance between the West’s conception of Palestinian society and the images I was making — the life I was living. In the news media, Palestinians were often portrayed as masked and violent or as disposable and lifeless: a faceless, miserable people.

But that’s not what I see when I am there. Instead, what I photograph is unconditional communal love, a rootedness and sense of historical belonging in the land, and a daily generosity and collective spirit that I rarely experience in America. Over the years, I’ve heard an endless number of stories passed down through generations that underscore a mosaic of social, cultural and religious pluralism.

Many of the photos of Palestinians I see today reflect the image of us as a suffering people. I see pictures of parents holding their ashen children in front of a pile of gray rubble or men being arrested by heavily armed Israeli soldiers or starving children with hands extended for food and water.

On the one hand, this type of photography documents the brutal reality of Israel’s indiscriminate violence in Gaza. But it also makes it easier for the viewer to see Palestinians as silhouettes who have always been this way instead of as people with entire lives, histories and dreams.

When images like these become the dominant depiction of a people, preconceptions become embedded in the minds of those who view them. In the case of the Palestinians, these insidious representations have paved the way for Israel’s wanton destruction of Gaza, for which Israel is now facing accusations of genocide in the international community’s highest court. In the context of violence and destruction, inflicting more violence and destruction becomes routine.

In reading Rouhana’s essay, I felt a connection to my own experience watching news footage about Haiti over the years. I, too, found the dissonance between what I experienced vs. what I’d seen represented after I visited Haiti for the first time jolting. I became even more cognizant of it when I visited in the country again in 2017. I was there to film my father as part of a documentary about my parents. By then, I had acquired the language to articulate a need to depict what I saw with diligence and care. I felt deeply conscious of who I’d be showing my footage to, and the fact that they’d likely never step foot in Haiti.

At the time, I didn’t know that visit would likely be my last. I don’t know when I’ll be able to travel to Haiti again. I ache to see where my parents grew up, the beaches and waters that made them.

This week’s recommendations & encounters:

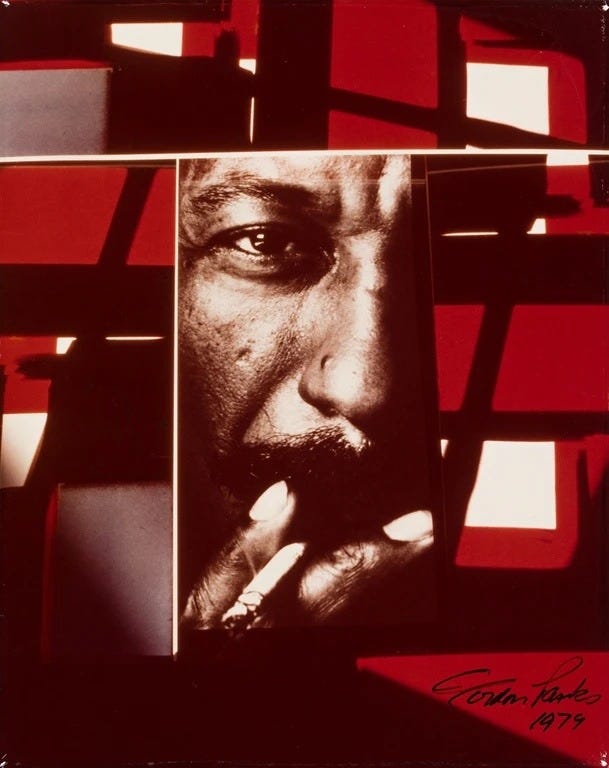

I. Last week, I wrote about an expanded and redesigned edition of photographer Gordon Parks’s Born Black (1971), the first book to combine his writing and photography. It publishes May 7. If you’re in New York, you can see the accompanying exhibition at Jack Shainman Gallery until April 20th.

A few exhibitions currently on view in Los Angeles that I’m especially looking forward to seeing: Desire to See, Agnes Varda’s photographs at Fahey/Klein (until April 13), Scratching the Moon at the ICA LA (ends May 12), and RETROaction (Part Two) at Hauser & Wirth’s downtown location (until May 5).

If you’re in London, Haymarket Books is co-hosting an event on March 15th to mark the launch of Against Erasure: A Photographic Memory of Palestine Before the Nakba.

II. A film - My Crasy Life, dir. Jean-Pierre Gorin

I studied documentary filmmaking in college, so I’m a real sucker for a fantastic documentary. I can definitively say that this is one of the best I’ve seen. Part documentary and part fiction, My Crasy Life (1992) is a gripping portrait of a Samoan street gang in Long Beach, California. It’s the type of film I would have been obsessed with when I was 19. The most thrilling documentaries toe the line between fact and fiction, and My Crasy Life is no exception. A film like no other.

As always, thank you for being here 💌

If you enjoyed this post, please don’t hesitate to share and/or subscribe! And if you’ve been here for a while, I urge you to consider becoming a paid subscriber. Permanent Daydream is truly a labor of love, and doing so is the most direct way to support me and my work. These weekly posts are just the beginning; there will be audio and additional content coming your way soon…