Spring has always been my favorite season. In the spring I feel the most alive and like myself. Something awakens in me, or else I am awakened.

Never summer, not with its languid heat and tar-like humidity. The times I have felt the most miserable in my life have, mysteriously, all taken place during the summertime. By summer’s end I find myself craving the slowness of fall and the sense of contemplation and transition it evokes in me.

Spring is a phase in the cycle—the endless spiral—that we can easily grow accustomed to, hardly pausing to give it a second thought. When I started gardening, the arrival of spring suddenly took on a mystical quality. Spring is when I could really get started; spring is when life would begin again.

I can’t think of a more innocent time of year. Beginnings blooming up everywhere, begging you to fall in love.

The spring equinox—rather than the first of January—has always felt like the true beginning of the year to me. In a previous post, I shared this breakdown of the seasons I’ve started referencing as a refreshing way to think about the passage of time, or at the very least, the year:

Spring reveals the lesson of patience. One waits for the gradual shift in light. Ever so slowly, the gears of the world turn. The clock leaps forward and suddenly, seemingly all at once, spring arrives.

But spring, of course, has a darker edge. In Greek mythology Persephone, daughter of Demeter, is kidnapped by Hades and carried off into the underworld. Stricken by grief, Demeter withdraws from the world, taking with her the crops and grains, the food of the earth. (In “Persephone Wanderer,” poet Louise Gluck writes, “Persephone is having sex in hell. Unlike the rest of us, she doesn’t know / what winter is, only that she is what causes it.”) Spring marks Persephone’s return, a forever bittersweet occasion.

In March of 1913, the composer Igor Stravinsky completed The Rite of Spring, now considered to be one of the most significant pieces of music of the 20th century. Rite follows a ceremony that occurs in celebration of spring’s return, in which a young virgin is chosen as a sacrificial victim and subsequently dances herself to death. The dissonant and jarring nature of Stravinsky’s score, in combination with Vaslav Nijinsky’s frantic choreography, immediately shocked audiences.

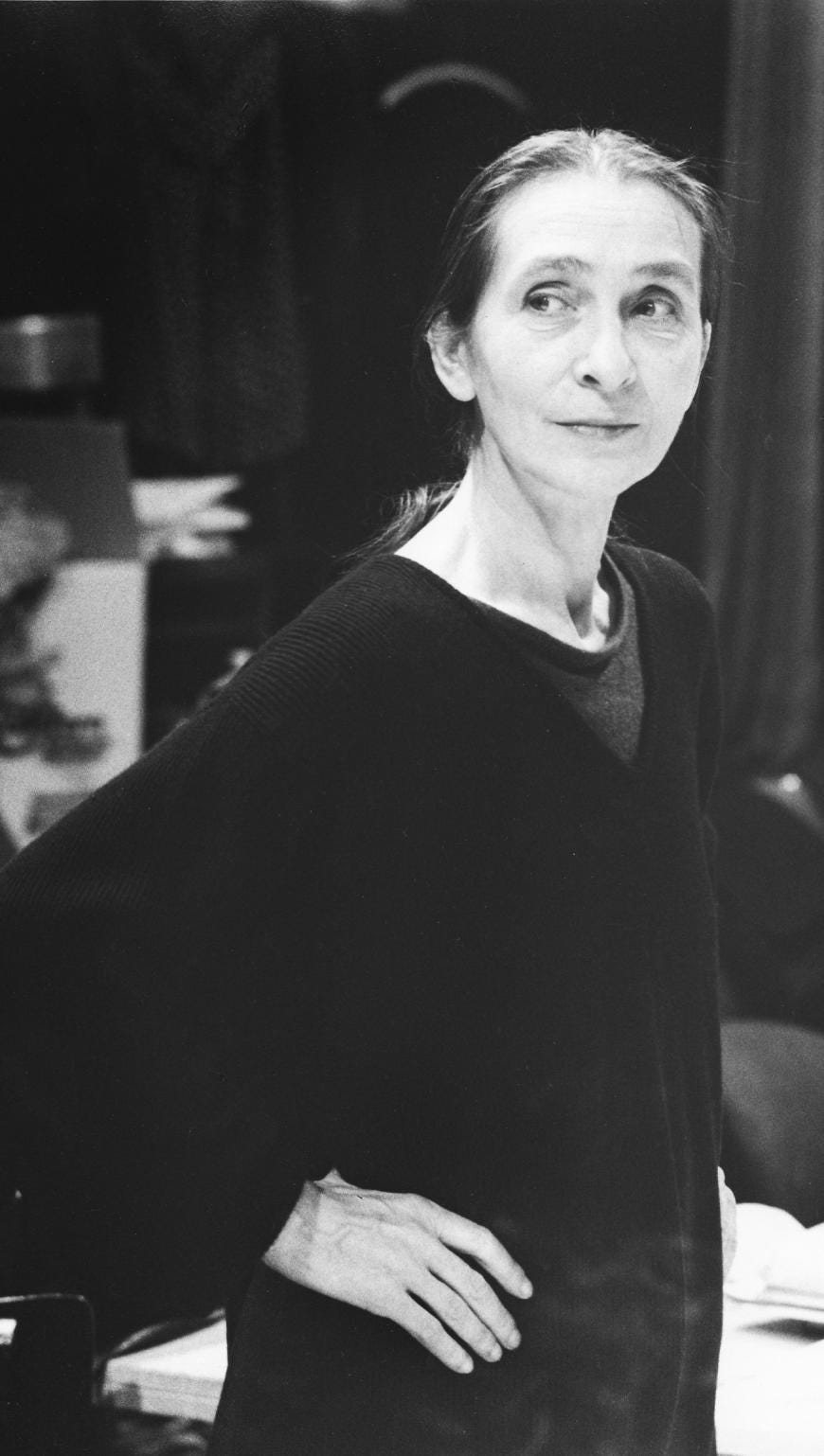

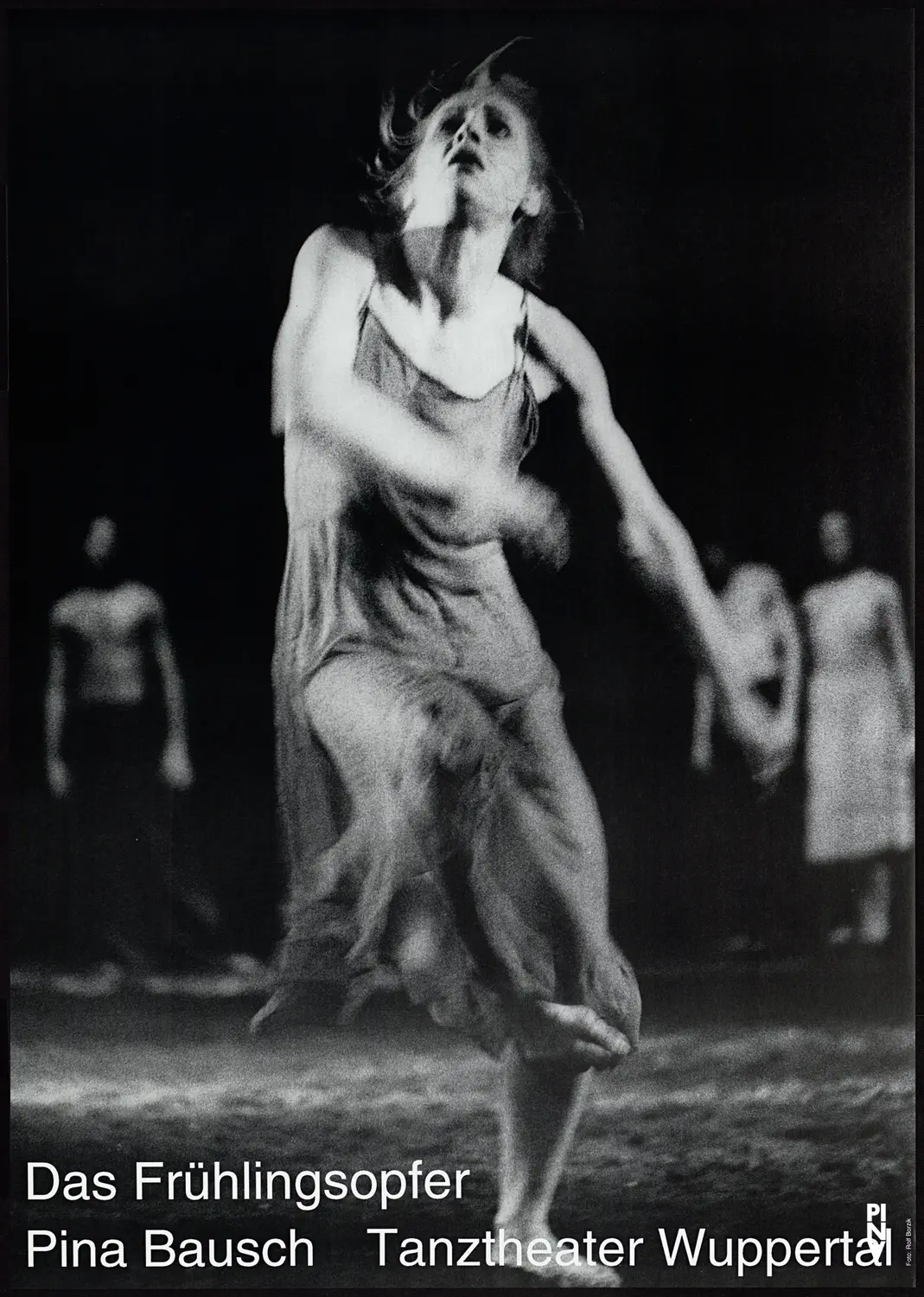

In 1975, the German dancer and choreographer Pina Bausch staged The Rite of Spring for her independent dance company, Tanztheater Wuppertal. Her version of the ballet, Frühlingsopfer, remains one of her most powerful and enduring works. In an essay for The Paris Review, writer and dancer Vanessa Manko shares how viewing Bausch’s Rite allowed her “to feel again” after an intense period of “angst and unease”:

On a stage covered in dirt, dancers honored the advent of spring and engaged in rituals of celebration and competition. A young woman was chosen as the sacrificial victim who must dance herself to death. In Bausch’s rendering of The Rite of Spring, the ballet is also a battle of the sexes. Men and women gathered in bands, sometimes antagonistic, sometimes tender, until the necessary choosing—by fate—of the one to be sacrificed. Raw, stark, and deeply theatrical, the choreography is atavistic in its deep, pulsing pliés à la second and in its darting, panicked pacing. It spoke to me on a visceral level. Here was a world far from the tame, codified world of ballet. Instead, there was wild fear, lust, despair, anger. There was an overall sense of disquiet embedded in the music and unleashed from deep within the dancers—in the pleading reach of limbs, the anguish of an arched back, the herdlike stamping of feet and, due to the strenuous nature of the dance, in the panting. And the dirt. So much dirt. Dirt clinging to clavicles, streaked across torsos and smudged, war paint–like, along shoulders, brows, cheekbones and lips. It seemed as if Bausch had communed with our ancient ancestors and brought all their primal fury into the modern world.

For Bausch, the question driving Rite was “how would you dance, if you knew you were going to die?”

What is life but a constant dance against death? What is spring but the entire world coming up from the dead?

Bausch passed away in 2009. Since the fall of 2021, the Pina Bausch Foundation, Sadler’s Wells Theatre, and the Senegalese École des Sables have collaborated to create an enthralling new staging of Bausch’s ballet. Two formidable women choreographed this new iteration of Rite: Germaine Acogny, known as the “mother of contemporary African dance,” and Malou Airaudo, who was a member of Bausch’s Tanztheater Wuppertal. Acogny and Airaudo also worked together to create a companion piece, common ground[s], a duet that appears before Rite.

Josephine Ann Endicott, artistic director for this revitalization of Rite, explains, “For a dancer, it’s one of the most wonderful things you could ever dance. It’s unforgettable. You feel every bone in your body. You feel the group. You are in the same community. It’s a group piece. We’re all sweating, we’re all feeling the same fear. And all the hairs start to stand up on your body. And then you know - that’s it. You have no chance to escape.”

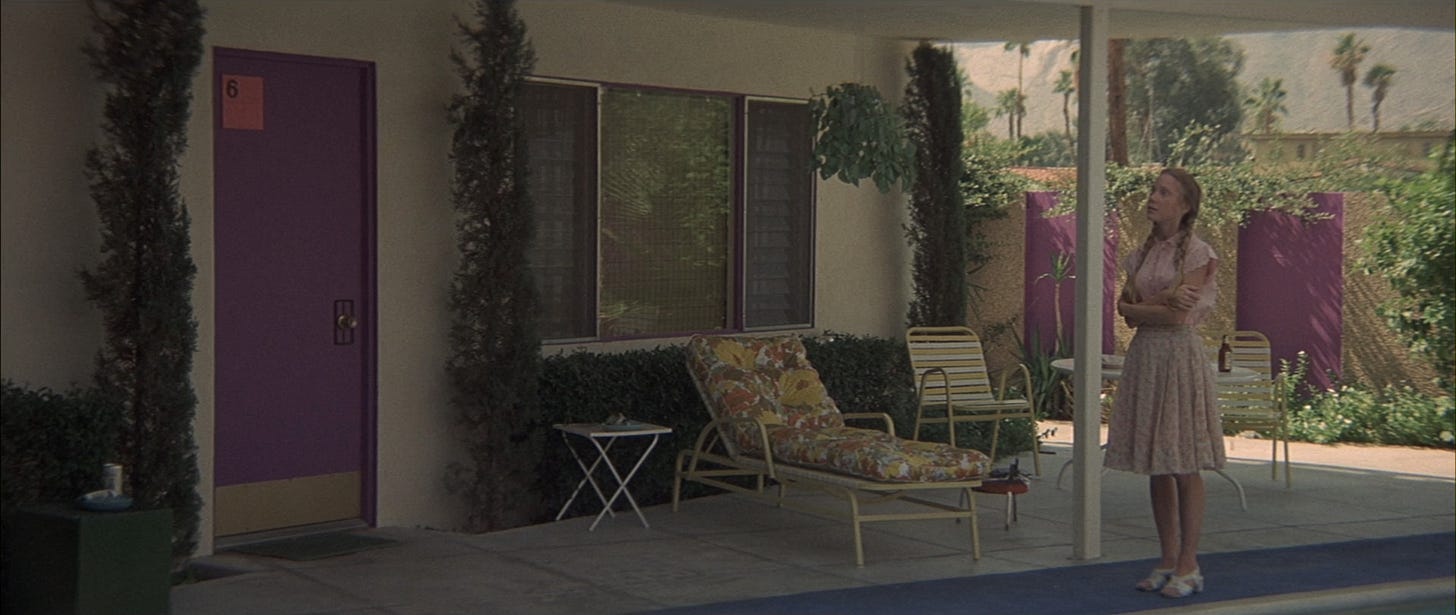

When I first watched Robert Altman’s fantastic 3 Women (1977), the film’s color palette immediately evoked spring. Even one of the film’s main characters, played by Sissy Spacek, has a name befitting the season—Pinky Rose.

3 Women follows Pinky as she befriends and begins to idolize Mollie (played by Shelley Duvall), a fellow nurse she meets while working at a health spa for the elderly. The film is filled with pale pinks and butter yellows, dusty blues and the soft purple of irises. (At one point in the film, Mollie asks Pinky if she likes the colors yellow and purple, her favorite because they remind her of irises).

It’s a strange, fever dream of a movie I could watch over and over again. Other films that evoke the season: Yasujiro Ozu’s Late Spring (1949) and Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), dir. by Peter Weir.

This week’s recommendations & encounters:

I. An exhibition - Spirit Movers at MoMA - until April 7

If you’re in New York, it’s your last chance to see Spirit Movers, an exhibition curated by fashion designer Grace Wales Bonner that explores “sound, movement, performance, and style in the African diaspora and beyond.” Each work of art featured was hand-picked by Wales Bonner, sourced from the museum’s vast collection. (We’re talking Agnes Martin, David Hammons, Betye Saar…) A reflection of Wales Bonner’s interdisciplinary and diasporic practice, Spirit Movers features work across a variety of mediums—sound, sculpture, painting, and more.

Wales Bonner’s taste is truly impeccable, a trait that translates seamlessly into her designs. How I wish I could see this show in person! Instead, I’ll be listening to this playlist Wales Bonner created to coincide with the exhibition.

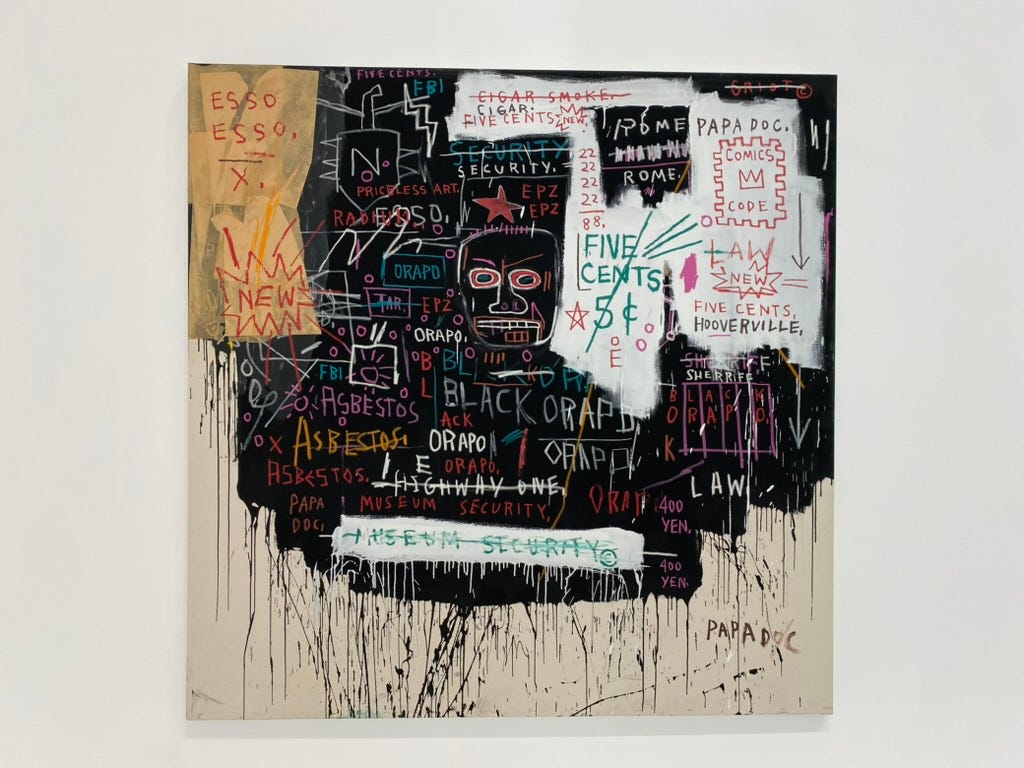

For those of you in LA, I highly recommend Jean-Michel Basquiat: Made on Market Street, the first exhibition focused exclusively on work Basquiat produced in Los Angeles. Made on Market Street is also a nod to Basquiat’s first solo exhibition in LA, which was hosted by Larry Gagosian Gallery in 1981.

Basquiat was one of the first—if not the first—artists I found myself drawn to when I first started developing an interest in art as a young person. There was—and still remains—an unshakable feeling of pride associated with him. He, too, was Haitian, a fact my mother always emphasized. Although they never met, my parents were in New York while Basquiat was, too. If he were alive today, he and my father would be nearly the same age.

When I stand in front of a work by Basquiat, I am always taken by the undeniable force of his vision and talent. He was so young when he started, so brilliant. I look and am deeply moved, but also saddened. I think of the hundreds of unmarked canvases, blank spaces aching to be filled. What if the art world hadn’t eaten him up? I wonder what he would be making now, and how time would have altered him.

II. A read - Rattlebone by Maxine Clair

I read this collection of eleven interrelated stories on the recommendation of a co-worker. My concentration for reading hasn’t been great this year, but Rattlebone by Maxine Clair easily transported and moved me with its rich language and unforgettable characters. Although Clair masterfully shifts perspectives throughout the novel, our main narrator is Irene Wilson, a clever and sweet young girl whose parents’ marriage is beginning to fall apart.

Originally published in 1994 and re-released by McNally Editions in 2022, Rattlebone is a deeply eloquent portrait of a young woman and the small 19050s town in Kansas that makes her. I love how Rattlebone isn’t a traditional coming of age story; Irene’s experiences are interwoven with the lives of her family members and neighbors. I’m shocked it took me so long to encounter this work, which upon reading instantly felt like a classic.

III. A treat - A funky spritz

If you’re a fan of matcha, I have a life-altering recommendation for you!!! Drama aside, I’ve been making / ordering these as my second matcha for the day. I can’t take credit for this; I thank the good people at Civil Coffee in Highland Park for introducing me to this delicious concoction. Lo and behold, the matcha spritz:

One shot of matcha

Ice

Sparkling water

(Now this is absolutely essential) A squeeze of lemon / lemon juice

Bonus ingredient: mint

It’s a lighter version of an iced matcha latte and something any decent coffee shop that serves matcha should be able to make. I’m honestly shocked it’s not more of a staple. The sparkling water makes it feel luxurious, a non-alcoholic version of a cheeky afternoon drink.

Lastly, I’ll leave you with a few spring-inspired poems:

As always, thank you for being here.

If you enjoyed this post, please don’t hesitate to share and/or subscribe! And if you’ve been here for a while, I urge you to consider becoming a paid subscriber. Permanent Daydream is truly a labor of love, and doing so is the most direct way to support me and my work.

I’ll see you in two 💌