What would it mean to reside in the space of a daydream? It’s a question I’ve been asking myself since I wrote an essay about gardening for the most recent issue of Worms Magazine. In it, I reflect on gardening’s relationship to pleasure and extraction. I was inspired by Jamaica Kincaid’s excellent writing, particularly her writing about gardening. (She wrote a memoir about trekking the Himalayas to collect seeds, which is pretty badass if you ask me.) There’s something very honest and unpretentious about her writing. She seems wholly unapologetic in a way that reminds me of my older Haitian aunties. Unbothered. But her sentences are perfect.

In an interview with Darryl Pinckney for the Paris Review’s “Art of Fiction” series, Pinckney asks her about her routine. Kincaid responds, “A routine would be too much like work, and I don’t really like to work, even though I work a great deal. All the things I do that might be considered work are really a form of play. Even when I’m ironing my sheets… I’m daydreaming.”

I’ve always been a daydreamer. Head in the clouds. Coming up with stories has always been a form of currency in my life, whether as a way to cope or ground myself in history, find an identity. Like many (probably most) writers, there is always some part of me that is a little bit elsewhere, a little bit removed, not completely comfortable or quite in the situation, collecting, daydreaming, my mind churning.

I thought about daydreaming, too, after reading this great profile of Joyce Carol Oates by my all-time favorite staff writer for The New Yorker, Rachel Aviv. I started reading The New Yorker in high school, and besides art critic Hilton Als, Aviv was the writer I became obsessed with. Oates is insanely prolific (she’s written something like 162 books in total) and the profile is tantalizingly centered around this question of a “secret” that drives Oates’s work, that oft-imagined “root” of a writer’s obsessions and self.) Oates is clearly writing in her head all the time. It sounds a little insane, and like a coping mechanism, but I also found the intensity of that commitment…. admirable?

My bio on all my social media accounts reads “permanent daydreamer” too, a phrase that popped into my head one day and just felt right. It wasn’t until I wrote the essay about gardening that I realized the things I love to do most—reading, writing, and gardening, a new pastime—feel like daydreaming.

All the things I do that might be considered work are really a form of play. I do really love that as a provocation, a prompt on a (perhaps better) way to live.

Art is important to me, and not just because I write about it. My previous newsletter, titled Ghosts in the Sunlight, was inspired by Hilton Als’s commencement speech at Columbia’s School of the Arts. Als, in turn, took the phrase from a Truman Capote essay in which Capote describes his experience watching actors embody the real-life characters from his 1965 novel In Cold Blood. To see memory embodied in the flesh troubled Capote; it also got at the heart of what art is about. Als writes:

By reading I discovered that art-making was a tradition that was bigger and no bigger than myself. I did not feel crippled by this knowledge; in fact, I was liberated by it: being an artist meant you were connected to other people—ghosts—who had been as moved by the enterprise of creating as you are now; evidence of their love was all the movies and performances and books and dances and music that informed your present so deeply and indelibly, acts of creation that stirred your imaginings to the point of making you wonder: How do I make the kind of film I want to see, write the kind of story or poem I want to read, perform the music, play, or dance that is expressive of the artist I’m meant to be?

I’ve loved this statement ever since I read it. Encountering and creating art has always felt like a ghostly, even mystical experience to me. The best art at least, and the best creative moments.

If you’ve made it this far, thank you so much for reading. This will be a weekly dispatch around a general theme, but I also hope it can be something that feels a little more open-ended. A conversation, an exchange, a meditation, a daydream 🌀

I’ll be sharing my end-of-year roundup soon, but I’ll leave you with one last daydream inspired source of inspiration.

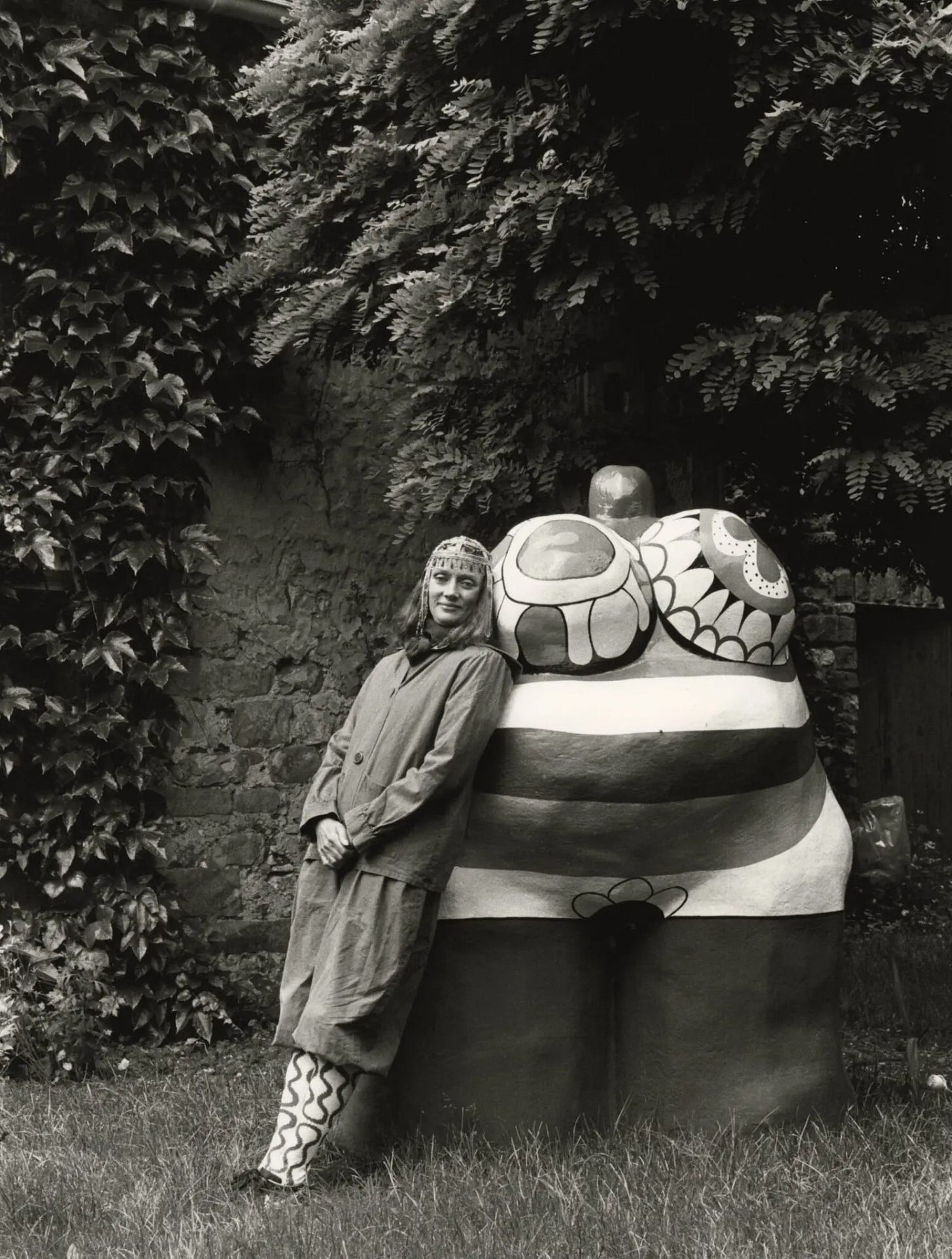

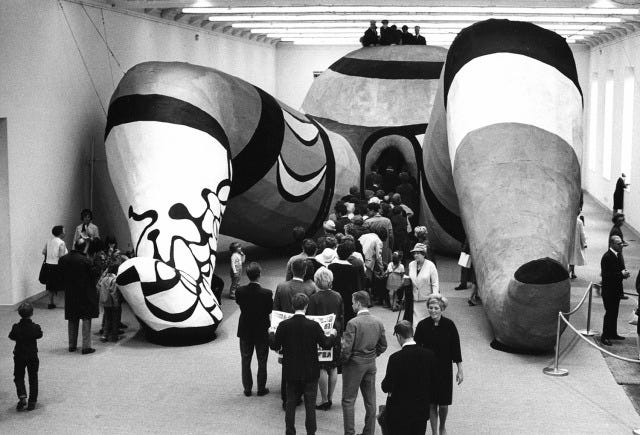

This summer, I discovered the work of artist Niki de Saint Phalle. She was a French-American sculptor and painter known for her Nanas, large-scale, colorful depictions of voluptuous women who represented femininity and motherhood, and her Tarot Garden, a vast sculpture park she envisioned inspired by Antoni Gaudí’s Parc Güell and the Watts Towers. To me, Saint Phalle’s work embodies the idea of the permanent daydream. There’s a refusal to “grow up,” a Bigness and emphasis on joy that I love.

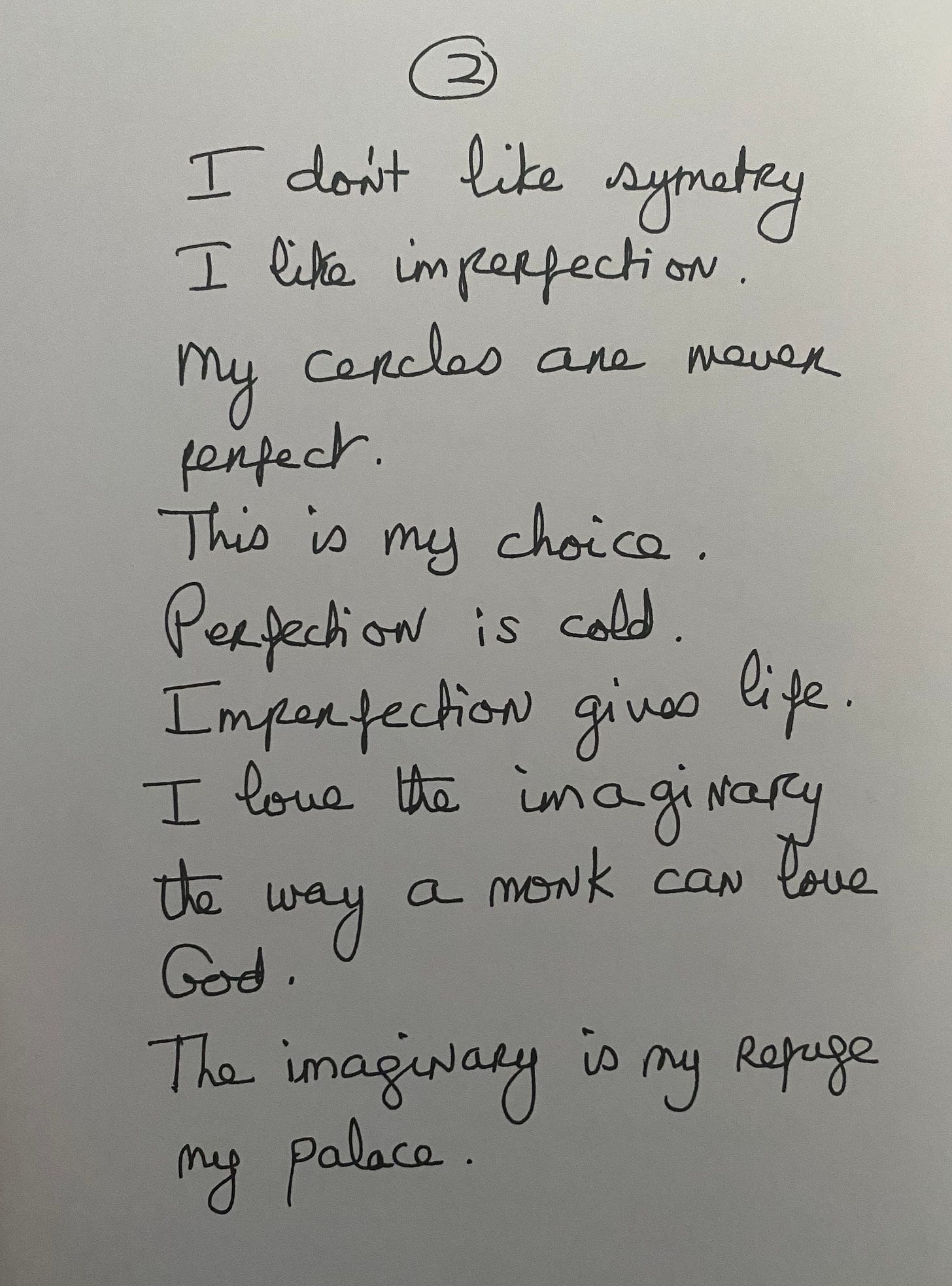

Early on, Saint Phalle was keenly sensitive to the question of the boundary between perception and reality. An early viewing of Kurosawa’s Rashomon provoked her to ask:

Is perceiving only personal?

Does that mean my version is only mine?

Where does that put reality?

Does it exist?

Is life a dream?

My dream that I can choose to make into a nightmare or song?

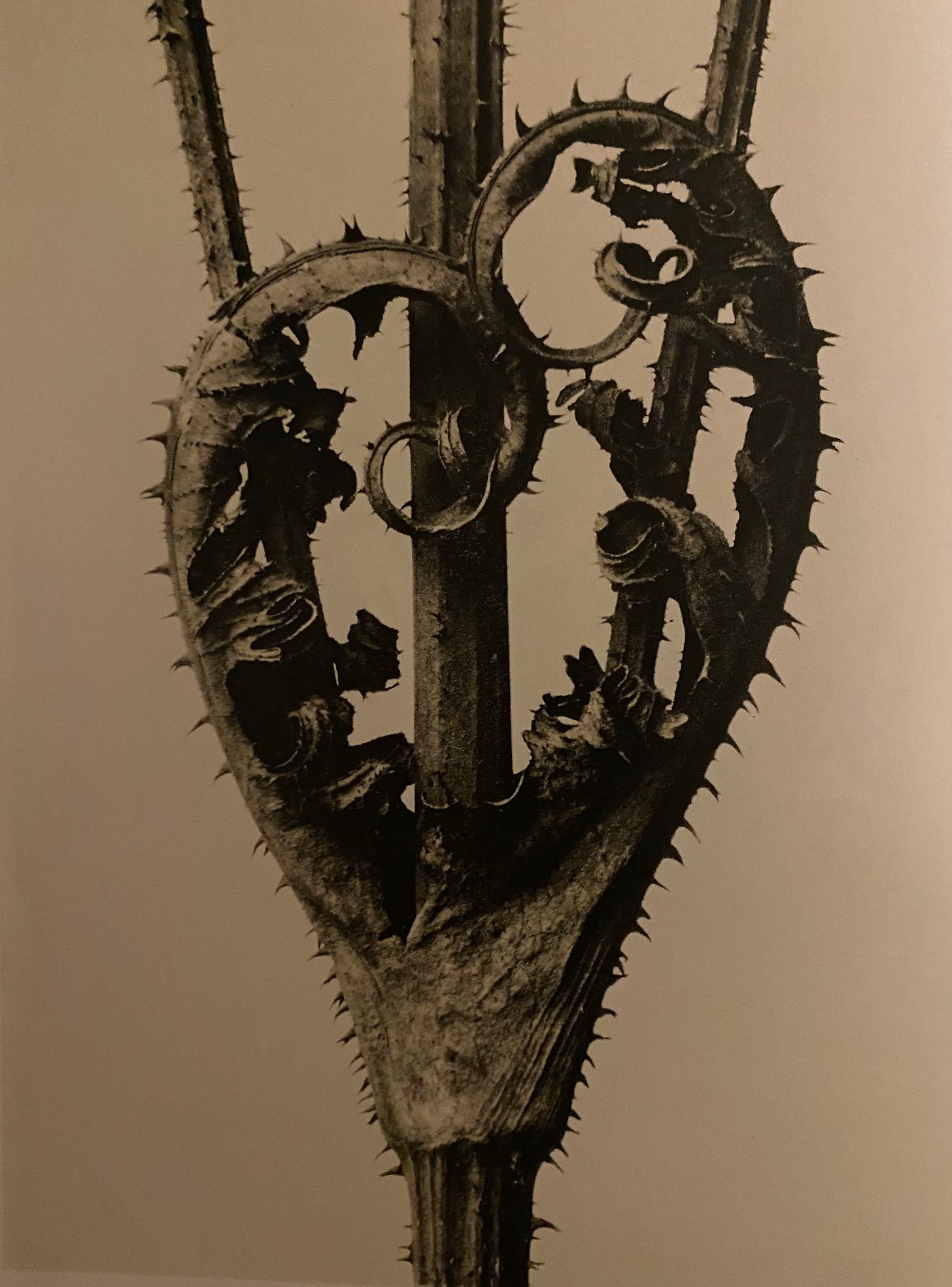

Saint Phalle’s earlier art had a harder edge to it; it involved shooting guns at painted collages. My dream to make into a nightmare or song. That, I think, is also what so much of art comes down to for those of us who make it. What will I do with this experience? How will I transform it, metabolize it? How do I translate it into a vision that other people can feel, and in her case, touch?