You see the same thing for days, months, and years and one day everything changes. There is no clear explanation why it is this day and not the others. No forewarning. Just a system of forces emerging, life running its course. Would it be better if you could prepare? Sometimes it is like the weather, this life, its patterns indecipherable to you.

I thought of the opening passage from Annie Dillard’s essay “Total Eclipse” the day I realized everything would change. The entire world opened up; I saw clearly, for the first time, what I had not wanted to see. Dillard writes:

It had been like dying, that sliding down the mountain pass. It had been like the death of someone, irrational, that sliding down the mountain pass and into the region of dread. It was like slipping into fever, or falling down that hole in sleep from which you wake yourself whimpering.

I was not yet inside the moment of change but could see it in front of me. A veil lifted from my eyes. It felt vast. As vast as the fog in this photograph. A vastness that drew me closer and closer but that I was not ready for.

And wasn’t looking through the viewfinder of a 16mm camera for the first time like falling in love? The world rearranged itself and suddenly I knew what to make of it. A clear before and after, like a click in the mind, the arrival of a thought.

If love gives you a new way of seeing then becoming a gardener has done that, too. I realize how little I know, entire species and phyla unidentifiable, entirely unknown to me. So much to be struck by. So much to behold.

Can I look without taking? Can I leave something be? Let myself be moved and then walk away, without the desire to capture or own it?

Life churns over and over again. Thousands of little deaths, births, beginnings and arrivals. So why can’t the same be said of love?

A year ago, I wrote:

Fall is here in Los Angeles. September comes, of course, with the usual heat wave. 105° in Hollywood and higher in the Valley. Summer’s never over.

But then the heat blooms and withers away, blooms and withers away until November.

“Don’t you miss the seasons?” I ask everyone who isn’t from here. My friends from the Midwest tell me the seasons there are cartoonishly distinct. And the winters. Soft snowy nights blanketed in white. I remember the first time I awoke to the gentle pat pat of flakes falling, a rare occasion in Georgia. I don’t know any other quiet such as that one.

I leave LA for one long weekend and come back to pomegranates and persimmons, Joni Mitchell’s “California” ringing in my ears.

A year later I find myself on the opposite side of the country, watching the world slow down around me. The autumn equinox begins after a flurry of late-summer activity. LA to Boston to Philadelphia to New York, Houston and then Atlanta. Finally, stillness. The leaves curl inwards. The apple tree bears fruit. Green turns into gold. My mother makes apple butter and cider vinegar. I can’t help but think of all of the citrus in California. The yuzus. The meyer lemons. So much heaven in California. Hell, too.

I traversed the seasons as I walked through Kim Chong Hak, Painter of Seoraksan at the High Museum. Born in Sinuiju, North Pyongan Province in 1937, Hak lived through an incredibly turbulent period in Korean history, including the colonization of Korea by the Japanese, the division of Korea, and the Korean War. His early work reflected this upheaval; he joined the avant-garde movement but soon became critical of its Western influence. Hak made the decision to reject contemporary trends after a stint in New York, turning instead towards Asian landscape traditions.

In the autumn of 1979 Hak left his family and moved into a lodge on Seoraksan, the highest peak in the Taebaek Mountains in South Korea. It was a crucial turning point in both his life and career. He cut off all contact with the exterior world:

In the summer of 1979, I ran away to Mt Seorak. I wanted to run away from my family and from the art world […] I wanted to live as I please, and paint as I please. And I wanted to be truly alone. That is why I live with the nature in Mt. Seorak. I spent all four seasons with the mountain, drawing spring in spring. summer in summer, autumn in autumn, and winter in winter.

Hak struggled immensely with feelings of self-doubt. He was convinced he’d failed as an artist. Nature quickly became Hak’s salve. Living in accordance with its rhythms revitalized him. Rather than following the whims of a forever-shifting art scene, he chose to be led by nature instead. The isolation allowed Hak to return to himself. His style changed. The abstraction was still there but expressed through visions of the landscape that surrounded him. This new phase gendered criticism; some even called him a “third-rate” artist.

Kim Chong Hak, Painter of Seoraksan reminded me of how my life changed once I started to develop a more intimate relationship with nature. Moving to Los Angeles ignited the reverence I feel for the natural world. I drove into the hills with one of my roommates the first week I moved. We picked oranges, lemons, and avocados. We brought them back and I spread them all out on the counter. Glimmering under the sun like jewels, they seemed far too precious to eat.

I can’t pinpoint exactly when my love affair with art began. (It’s the same with writing. For as long as I have been alive this urge has resided within me. I spent years tapping it down yet it refused to listen, continuing to roar inside of me. Love brought it back.)

It must have been as a child. The walls of my childhood home were filled with paintings from Haiti. Those paintings are the foundation of the collection I’d like to build one day. There’s a painting that hung in my parents’ bedroom I remember vividly, of two women bathing. I can still recall the shade of blue that sheathed them.

My longest love affairs: looking and writing. How I loved to be moved as I look at a work of art. I saw The Gates of Hell at the Rodin Museum in Philadelphia and burst into tears. It was like Rodin travelled across time and space in order to whisper in my ear. I had seen Rodin before, even in Paris, but it was here, in Philadelphia of all places, where he struck my soul.

I’m a firm believer that sometimes a work of art has to hit you at the right moment in order for you to understand it. You have to be open, completely vulnerable to what an artwork might evoke in you. Anxiety. Melancholy. Trepidation. Awe. There are works of art that I love simply because they awakened something in me.

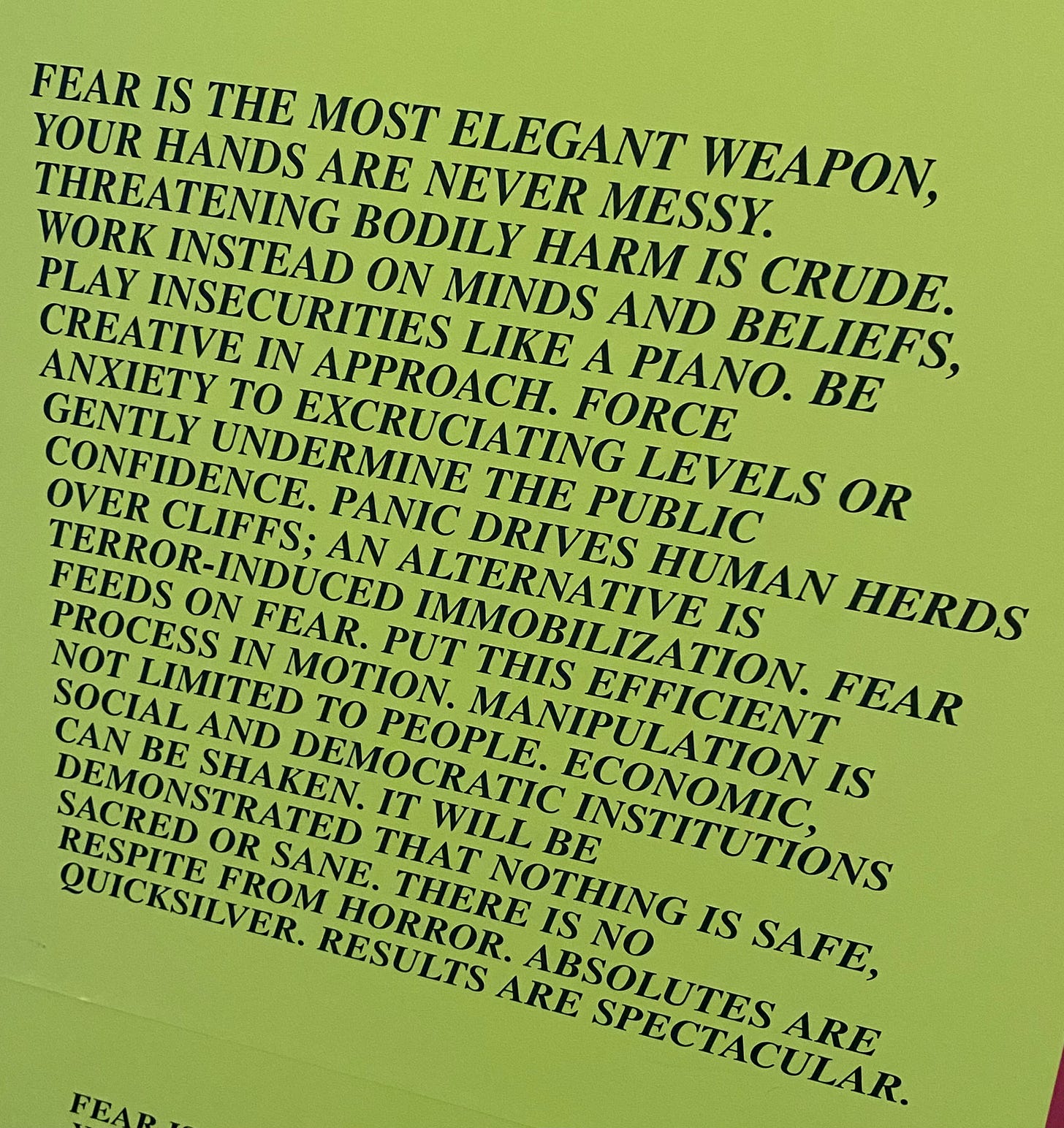

One of the first works of art that engendered this feeling was Jenny Holzer’s Inflammatory Essays (1979-82) series. I probably came across this work while scrolling on Tumblr. I must have been thirteen or fourteen. I’d recently abandoned my foray into religion, replacing it with an obsession with music, art, and poetry. (I was never a wholehearted believer. It was the theatricality and symbolism that quickened my heart.)

As a writer I found it incredibly exciting that a work of art could be comprised of only words, a deceptively simple collection of phrases. Phrases that provoked and had an immediacy I had only experienced through poetry. The fervor of the language, as well as its sharpness, enticed me. I was hooked.

I keep returning to Ariana Reines’ recent book Wave of Blood, a collection of poems, essays, and lectures written between October 2023 and April 2024. I haven’t been able to stop thinking about Reines’ work after reading her poem “Truth or Consequences” in Pathetic Literature, a fantastic anthology edited by Eileen Myles. I know I’m experiencing a great work of art when my body physically reacts to it. It happens rarely but when it does, I take note. That poem literally took my breath away. I was a different person when I reached the end of it.

I admire Reines’ honesty immensely. I don’t think there’s any poet writing like her today. She leaves everything on the page: her fury and fear, her desperation and suffering. I read her work and remember what it means to write from the body. There’s a ferocity to her work I love, one rooted in a willingness to be open-hearted, to say the “wrong thing,” to search for the soul in a time that increasingly feels soulless. She’s the only person I’ve read who has managed to articulate what it’s like to be alive in this moment in time. I found myself underlining nearly every sentence, dog-earing every other page because her words felt so vital and true.

I think about the heart and the soul often. (Emerson once wrote, “The soul is the perceiver and revealer of the truth. We know truth when we see it, let skeptic and scoffer say what they choose.”) Sometimes I wonder if I’m corny for doing so. Cynicism often seems like the safer choice. It involves less risk and disappointment. I’ve tried to steel myself against the world many times. I’m never successful. It goes against my nature. I feel most powerful when my heart and mind are aligned.

I felt relief when reading Wave of Blood because Reines speaks plainly about the heart and soul. She writes:

It’s easy to get imprecise, and to lose the essence of the thing when we start abstracting and intellectualizing. I’m not saying that we should take away our rigor or our precision, or that we should turn off our brains somehow. But we have to guard it carefully, because the brain goes crazy with this stuff. It’s being assaulted by absolute and total carnivorous brutality, and that breaks the mind down and the heart can’t stand it. No human heart can stand to see what’s happening right now.

[…]

I’ve noticed, in the art world […] thinking is allowed. But people’s hearts are totally calcified. The heart is at present a taboo. It’s become a taboo.

It feels a little stupid, doesn’t it? To talk about the heart? We don’t practice speaking from it and we have no customs for speaking from our hearts in public. […] It’s always connected to intoxication or excess or some kind of horror or accident—that a person speaks from the heart.

The level of hatred coursing through this country frightens me. I feel the weight of this hatred when I move through the world. A vibration I sense in airports and grocery stores. I can feel my body trying to protect me. I cross my arms. I don’t smile. I avoid a stranger’s gaze.

I grasp for acts of kindness. I nearly cry at the airport as I watch a mother and father drop off their son at the gate. Suddenly, out of nowhere, I feel protective of this child. I feel nervous for him. I remember that I was a child once. That everyone sitting around me was, too. When the boy almost forgets his suitcase, he makes a joke and we all laugh. I admire his bravery. I hear his father say, “Well, it’s too late to back out now.” The flight attendant assures the father that his son is in good hands.

All this hatred is corroding our hearts and souls. Hate degrades the spirit; love buoys it.

The Trump Administration is actively attempting to erase and rewrite history by targeting major museums and cultural institutions that refuse to adhere to its ahistorical agenda. On March 24, Trump issued an executive order titled “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History,” which placed Vice President JD Vance on the Smithsonian’s board of regents, allowing him to oversee the removal of “improper, divisive, or anti-American ideology” from the Smithsonian. (I’d love to know who is behind the statue of Trump and Jeffrey Epstein holding hands, originally titled Best Friends Forever and renamed Why Can’t We Be Friends? The statue was removed but reinstalled eight days later. It’s significant that the statue is located at the National Mall, home to the Smithsonian.)

On July 24, painter Amy Sherald cancelled her exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery after learning that the museum was considering removing her painting Trans Forming Liberty (2024) from the exhibition. Four days earlier, the Smithsonian’s Molina Family Latino Gallery, which has functioned as the temporary location of the forthcoming National Museum of the American Latino, cancelled ¡Presente! A Latino History of the United States, an exhibition that, in the words of director Jorge Zamanillo, offered a “101 on American Latino presence in the United States and how it fits into the larger American history narrative.”

On August 21, the White House published an article titled “President Trump is Right about the Smithsonian.” The article—really a hit list—targeted a number of exhibitions, including Thriving in Diversity: Latinas and Latinos with Disabilities, for featuring content from “a disabled plus-sized actress” and “an ambulatory wheelchair user who educates on their identity being Latinx, LGBTQ+, and disabled.” Other institutions on the list included the American History Museum, the National Museum of African Art, and the Museum of American Art.

Images carry meaning. They can transform our understanding and reveal truths previously unknown to us. Images have been used to shape who we see as belonging in this country since its founding. Democracy, art, and citizenship have always been intertwined.

The most photographed man in his time, Frederick Douglass was keenly aware of the role images played in challenging racial injustice. In 1861, he delivered his now-famous lecture “Pictures and Progress,” in which he declared:

As to the moral and social influence of pictures, it would hardly be extravagant to say of it, what Moore has said of ballads, give me the making of a nation’s ballads and I care not who has the making of its laws. The picture and the ballad are alike, if not equally social forces-the one reaching and swaying the heart by the eye, and the other by the ear. As an instrument of wit, of biting satire, the picture is admitted to be unrivalled. It strikes human nature on the weakest of all its many weak sides, and upon the instant, makes the hit palpable to all beholders.

Douglass spoke of photography’s potential to counter stereotypical and degrading depictions of African-Americans. Image-making was essential to the fight for abolition.

One of the most iconic photographs of Douglass’ time depicts a formerly enslaved man whose back bears deep scars from years of brutal whippings. Known as The Scourged Back, the photograph was taken at a Union camp near the Mississippi River, where the enslaved man, identified as ‘Peter’ or ‘Gordon,’ found refuge after his escape.

Widely circulated during the Civil War, the photograph served as powerful evidence of slavery’s brutality. It’s an image that speaks directly to the history of racial violence in the United States. Last month, the Trump Administration ordered its removal from the Fort Pulaski National Monument, a Civil War battle site in Georgia.

All of this has precedent. In September 1933, eight months after Hitler rose to power, the Nazi Party established the Reich Chamber of Culture, headed by Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels. As part of their efforts to gain control over German cultural life, the Nazi Party removed thousands of works of art from Germany’s state-owned museums. The works of art, many of them by internationally renown Modernists such as Max Ernst and Paul Klee, were deemed “un-German.” Goebbels presented these works in a 1937 exhibition titled Degenerate Art. Also on view was the Great German Art Exhibition, a selection of Nazi-approved art presented at the newly constructed Haus der Kunst, the first major architectural project commissioned by the Nazi Party. (There is a certain art-historical poetry to the fact that the late, great curator Okwui Enwezor would lead the museum sixty-four years later.)

In Art on My Mind: Visual Politics, bell hooks writes:

I was asked whether I thought art mattered, if it really made a difference in our lives. From my own experience, I could testify to the transformative power of art. I asked my audience to consider why in so many instances of global imperialist conquest by the West, art has been either appropriated or destroyed. […] It occurred to me then that if one could make a people lose touch with their capacity to create, lose sight of their will and their power to make art, then the work of subjugation, of colonization, is complete. Such work can be undone only by acts of concrete reclamation.

And Toni Morrison reminds us, in one of her last lectures, that “all art is dangerous”:

I want to remind you of the history of artists who have been murdered, slaughtered, imprisoned, chopped up, refused entrance. The history of art—whether it’s music, written, or what have you—has always been bloody, because dictators and people in office, and people who want to control and deceive, know exactly the people who will disturb their plans. And those people are artists. They’re the ones who tell the truth and it’s something that society has got to protect. When you enter that field […] it’s a dangerous pursuit and somebody’s out to get to you. You have to know it before you start, and do it under those circumstances because it’s one of the most important things human beings do. That’s what we do.

And it’s not just artists who are being targeted. In August, The National Endowment for the Arts cancelled its creative writing fellowship.

As frightened and sad as I am, I refuse to let this administration squash my hope. I have never believed more in art than I do now. This administration wants to divide us in order to solidify its power. It wants us to become immobilized with fear. I refuse. I know that artists will speak up—are speaking up—and it is my duty to listen. Because, as Toni said, it’s what we do.

A gallerist told me that he and other gallery owners, untethered from federal funding, have a duty to amplify the voices the administration is trying so hard to erase. I wish we were not living through this moment, but I have no doubt that writers, artists, curators, and cultural luminaries of all kinds will create work that allows us to reflect and respond. On a personal level, I feel a duty to keep watch and make sure their efforts are recognized.

Exhibition recommendations:

If you’re in Los Angeles, there are two incredibly timely exhibitions on view this month: An America at The Box (until Nov 1) and Monuments at MOCA, which opens October 23rd and closes May of next year. An America, curated by Mitchell Algus and first exhibited at his gallery in New York, includes works by Barkley L. Hendricks, Dash Snow, and Robert Mapplethorpe. I found the press release for the show refreshing. No unnecessary jargon, just straight to the point:

An America is an exhibition curated and first exhibited by Mitchell Algus at his gallery in NYC. Traveling this exhibition to our gallery in LA is an act of art world solidarity. And yes, you are right in thinking that we just did an exhibition, Burn Me!, that was a politically charged show. We will continue. America needs to see this work now. They need to see political artwork that confronts the political catastrophe that is happening in this country. This exhibition is a collection of bold works, both historical and recent, that address the corrupt fascists that have run this country for decades. Trump is just the most recent, and in many ways the most extreme, example of said fascism. Mitchell Algus and The Box choose to show this work and not shy away from the difficult political work being made and much ignored. An America is art exhibition as political statement. A political statement against the capitalist greed that drives much of the Art World, and much of the Western World we live in.

MONUMENTS combines newly-commissioned works by Bethany Collins, Abigail DeVille, Karon Davis, Stan Douglas, Kahlil Robert Irving, Cauleen Smith, Kevin Jerome Everson, Walter Price, Monument Lab, Davóne Tines, Julie Dash, and Kara Walker with decommissioned monuments, many of them Confederate, from around the country. So many favorites here; I’m not planning on missing this one!

Other LA exhibitions: Derek Fordjour’s Nightsong and Sam Gilliam: Constructions in Color, 1978-1981 at David Kordansky (closes October 11), Dear Mazie, at CAAM (ends March 1), inspired by the life and work of Amaza Lee Meredith, the first known Black queer woman to practice as an architect in the United States, Suchitra Mattai’s Fables, Guineps and the Sweetness of Unknowing and Esmaa Mohamoud’s What Does Webster’s Say About Soul? at Roberts Projects (ends Nov 15), It Smells Like Girl (ends Nov 1) at Jeffrey Deitch, Frank Romero: California Dreaming at Luis De Jesus Los Angeles (ends Oct 25), Corita Kent: The Sorcery of Images (closes Jan 24) at Marciano Art Foundation, and Ofelia Esparza: A Retrospective at Vincent Price Art Museum (opens Oct 18).

NY exhibitions: Hank Willis Thomas: I AM MANY at Jack Shainman Gallery (ends Nov 1), Downtown/Uptown: New York in the Eighties at Lévy Gorvy Dayan (ends Dec 1), co-curated by Mary Boone (what a comeback she’s having!), Body Vessel Clay: Black Women, Ceramics & Contemporary Art (until Dec 6) at the Ford Foundation, Graciela Iturbide: Serious Play and Naima Green: Instead, I spin fantasies at ICP (Oct 16 until Jan 12), Nicole Eisenman: STY at 52 Walker (opens Oct 30), Sasha Gordon: Haze at David Zwirner (ends Nov 1), the Gaza Biennale at Recess (ends Dec 20), Data Consciousness: Reframing Blackness in Contemporary Print (ends Dec 13) at Print Center New York, Tom Lloyd and From The Studio: Fifty-Eight Years of Artists in Residence at the Studio Museum, which reopens November 15th.

I had the pleasure of working on Kahlil Joseph’s first feature film, BLKNWS: Terms and Conditions, which is finally out in the world! I worked on the film as a contributing writer. (My first film credit!) I’m beyond thrilled that folks will finally have a chance to see it. Here is a teaser for the film. It premiered at Sundance and had a wonderful reception at this year’s Berlinale and the New York Film Festival. It’s out November 2nd.