I had a whole plan for this post. A theme like always, meant to summarize my life during the past few months. A list of everything I’ve consumed—what I’ve been reading, watching and listening to.

For a while that’s how I envisioned this newsletter. But I don’t want to do that anymore. I’ve loved the research process of creating this newsletter but finding things in my life to share and distill every week started to feel extractive. And Substack has since grown into a platform that has started to feel a bit icky to me too, a combination of what Twitter used to be and Instagram, a place now overrun with influencers peddling gift guides full of affiliate links. (See Brandon Taylor’s post voicing a similar sentiment.) No shade, but I have bigger visions for Permanent Daydream.

That being said, there is more coming! I have a book to write, so while I’m away you’ll be hearing from some of my favorite artists and thinkers. Some of them will be dear friends of mine, some of them strangers. All of them will be people who embody Permanent Daydream and the quote that started all of this to begin with, from author Jamaica Kincaid: “The things I do that might be considered work are really a form of play. Even when I’m ironing my sheets… I’m daydreaming.” The idea that a sense of curiosity, wonder and play is essential to creating a meaningful life. I believe in this wholeheartedly because as an artist this has saved me, but also because I know this belief can be enlivening and transformative for any human being.

I’ve interviewed a host of incredible authors, curators and artists throughout the last three years. I want to keep pouring energy into that act while sharing more of these moments with you. That has meant re-envisioning how I want to use this platform moving forward. I want Permanent Daydream to be an extension of that work—less of me (I’m not that interesting, anyway!) and more of the people, as cheesy as it sounds, who inspire me.

I’m in Arcata, CA, one of my favorite places in the entire world. I was last here three years ago. That trip cemented my love of California, particularly its coast.

I’m surrounded by redwoods. Apparently the largest tree in the world is not far from here, but they don’t advertise the location for fear of people climbing it.

It’s a hard lesson to remember, but I started to gain freedom when I realized life wasn’t something to be won. I used to be so hard on myself if something difficult happened. I used to clutch onto life, thinking that if I could just control every aspect of it I would be fine. Turns out that no matter how much you plan or prepare, shit will always hit the fan.

I went to Harvard and was raised in a household that expected nothing less of me. Sometimes I have to remind myself how crazy that is, to have been told to achieve something statistically insane. (I applied regular admission and that year something like only 2.6% of applicants got in.) I was on a hamster wheel of aimless ambition for so long and it almost killed me. For years I stifled the artist in me. When that person began to emerge it felt like night and day. The beginning of a new life.

The path of an artist is no easy one. It’s been interesting to realize, as I’ve gotten older, that most of it comes down to a refusal to give up and a willingness to believe in yourself when no one else does. In committing to the life of a writer I commit to a journey that is arduous but so rewarding. I am the best version of myself when I write: dedicated, curious and completely open.

Turns out there is no grand and elaborate point system, just a constant ebb and flow. Becoming a gardener has shown me how everything has its time and its place. Our lives are like that, too.

Last year I read What Is Found There: Notebooks on Poetry and Politics by the late poet Adrienne Rich, in which Rich reflects on poetry’s political implications. Rich saw poetry as a vital human resource—as necessary as food or shelter—and lamented how little we value it in American culture:

Most, if not all, of the names we know in North American poetry are the names of people who have had some access to freedom in time—that privilege of some which is actually a necessity for all. The struggle to limit the working day is a sacred struggle for the worker’s freedom in time. To feel herself or himself, for a few hours or a weekend, as a free being with choices—to plant vegetables and later sit on the porch with a cold beer, to write poetry or build a fence or fish or play cards, to walk without a purpose, to make love in the daytime. To sleep late. Ordinary human pleasures, the self’s re-creation. Yet every working generation has to reclaim that freedom in time, and many are brutally thwarted in the effort. Capitalism is based on the abridgment of that freedom.

Rich was writing in 1993 before social media took over our lives, and I wonder how much of the poetry of daily life we miss out on because we’ve sequestered our freedom and presence, given it over to these corporations that want our time because they want our money.

(I know this is a familiar rant, so boring, but this way of living is so soulless, so unsexy!)

I have felt the power of poetry acutely many times over. It has everything to do with presence and being embodied in the physical world. The immense joy and freedom I feel as I watch life emerge day-by-day, often into something that brings me wonder and takes my breath away.

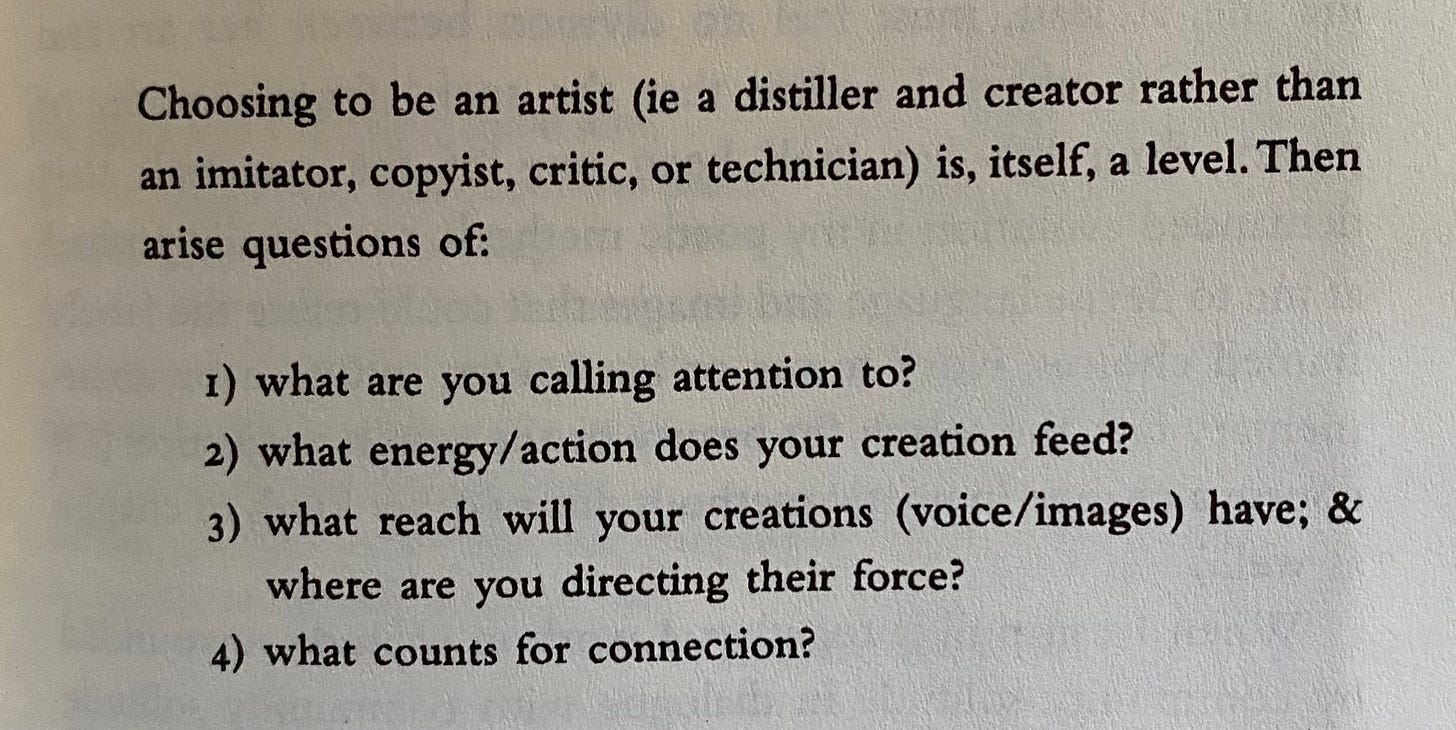

To end, I’ll leave you with these questions from Adrienne Rich:

Happy New Year.