If you know me, you know beauty is extremely important to me. I don’t always know why I find something beautiful, but it is always an embodied experience that has the clarity of truth. Something calls out to me, ringing out like a bell. I look and am drawn closer.

Starting Permanent Daydream has been a way for me to carve out space to elaborate on beauty in some form or another each week. To be a permanent daydreamer is to refuse to let go of this capacity for seeing more widely and deeply, despite the harshness of the world. I’m not saying I always succeed at it; but searching for beauty—staying silent and still enough to let it call out to me—has changed how I move through the world. It brings me pleasure and has expanded my capacity for presence, providing that ever-elusive experience of awe.

But what is beauty, anyway? Is it the perfectly symmetrical face? Is it luxury as expressed through cashmere or leather, something finely made? Or is it something simple, like a sunset or a laugh or a palm tree?

And should we even value beauty to begin with, when it is so easily weaponized? In Easy Beauty, philosopher Chloé Cooper-Jones explores what beauty means as someone who lives with a rare congenital condition, one that prompts her colleagues to debate as to whether or not her life is even worth living. In living in a body deemed monstrous by not only society but also those closest to her, Cooper-Jones writes how she developed a defense mechanism, a “neutral room” in her mind that protected her from the brutal judgements and actions of others as well as the daily pain she lives through as a byproduct of her condition. Creating this room protected Cooper-Jones but also shut off her capacity for letting in beauty. Beauty became associated with aesthetic perfection, something she felt she could never identify with. Her defense against beauty even became intellectual:

Anything of […] mass appeal must be, by definition, lacking—merely facile pleasure, or what British philosopher Bernard Bosanquet called easy beauty. Easy beauty was apparent and unchallenging: “A simple tune; a simple spatial rhythm… a rose; a youthful face, or the human form in its prime, all these afford a plain straightforward pleasure…” Conversely, difficult beauty, wrote Bosanquet, required more time, patience, and a higher amount of concentration. Our ability to appreciate difficult beauty depended on our education, insight, and endurance, and our capacity for attention. In difficult beauty, one often encounters intricacy, tension, and width. […] Difficult beauty also required us to stay in a state of “high tension feeling,” and it is our own weakness—the “weakness of the spectators,” says Bosanquet, taking the phrase from Aristotle—that causes us to shrink from the challenge of difficult beauty.

Initially, Cooper-Jones resists anything she deems to be an “easy” form of beauty, seeing herself as superior to it. But at a Beyoncé concert in Milan—an event she initially resists attending—her understanding of and relationship to “easy” beauty changes. “I look out from the stage at an ocean of people,” she writes, “all united in an experience of blunt, triumphant beauty, and I think of all the ways I’d nearly rationalized myself away from this, of how many layers of superiority, theory, pretense I’d used to build up my little house of self-regard that kept me inside, shielded.” Beauty does that: dissolves our edges and the boundary between us and the other, the internal and external.

One of my favorite books about beauty is Japanese art historian and philosopher Yanagi Sōetsu’s The Beauty of Everyday Things. Sōetsu is known for founding the mingei, or Folk Art Movement, in Japan. Sōetsu urged an appreciation for folk crafts, whose creators “are not famous artists but anonymous artisans” who make ordinary objects for practical, daily use. In his essay “What Is Folk Craft?,” written in 1933, Sōetsu laments the lack of beauty found in most ordinary objects:

In recent times a shadow has fallen on our sense of beauty, on our aesthetic sensibility. There are undoubtedly many reasons for this, but one is certainly the fact that our everyday utilitarian utensils and implements have become so ugly. It is these ugly things that surround us throughout the day, from morning to night—the clothing we wear, the utensils we eat from, the furniture we make use of. Without our realizing it, these unattractive objects have had an enormous impact on our sensitivity to beauty.

We no longer look upon objects as we used to, which is undoubtedly due to their poor quality. In the past, everyday objects were treated with care, with something verging on respect. While this attitude may in part have been a result of the scarcity of goods in past times, I believe it principally resulted from the honest quality of their workmanship and the fact that the more an object was used, the more its beauty became apparent. As our constant companions in life, such objects gave birth to a feeling of intimacy and even affection. The relation between people and things then was much deeper than it is today. When a person could point to what he was wearing and say, ‘This belonged to my grandfather,’ it was a source of pride. These days, however, the careless way things are made has robbed us of any feeling of respect or affection.

I look at photographs of my mother in the 80s and 90s, the beautiful clothes she wore, and feel a true sense of loss. How I wish I could have inherited them, the shoulder padded jackets, the worn-in denim, the extravagant hats. It’s not only about the idea of owning them, though. It’s about what it would be like to feel the mark of time, a sense of my mother in the past. A whiff of perfume, a stray receipt or subway ticket. Things I’m sure I would find beautiful and want to keep.

Sōetsu goes on to say that when we only appreciate beauty in the realm of fine arts, we lose a sense of appreciation for the beauty of “utilitarian crafts.” As a result, “our aesthetic sense [becomes] severely impaired owing to the fact that beauty and life are treated as separate realms of being.” Beauty is “no longer viewed as an indispensable part of our daily lives.”

What happens when beauty becomes sequestered, or is seen as an aspect of living only relevant to the rich, elite, well-connected, or privileged? Questions of taste and curation inevitably arise. Again, a question I think about all the time: Who has access to beauty?

Attention and beauty are related; both require you to adjust your perception of the world. Drawing from the work of fellow philosophers Simone Weil (who I wrote about last week) and Iris Murdoch, Elaine Scarry writes of a “radical decentering” that occurs when we are in the presence of something beautiful in On Beauty and Being Just:

When we come upon beautiful things—the tiny mauve-orange-blue moth on the brick, Augustine’s cake, a sentence about innocence in Hampshire—they act like small tears in the surface of the world that pulls us through to some vaster space […] they lift us (as though by the air currents of someone else’s sweeping), letting the ground rotate beneath us several inches, so that when we land, we find we are standing in a different relation to the world than we were a moment before. It is not that we cease to stand at the center of the world, for we never stood there. It is that we cease to stand even at the center of our own world. We willingly cede our ground to the thing that stands before us.

Scarry draws on Murdoch’s 1967 lecture “The Sovereignty of Good over Other Concepts” to suggest that this experience of “unselfing” can lead us to act with greater ethical clarity. “How we make choices, how we act, is deeply connected to states of consciousness,” writes Scarry. When our ego—the never-ending litany of stories we tell about ourselves—disappears, beauty rushes in, reminding us of what we value and therefore want to protect.

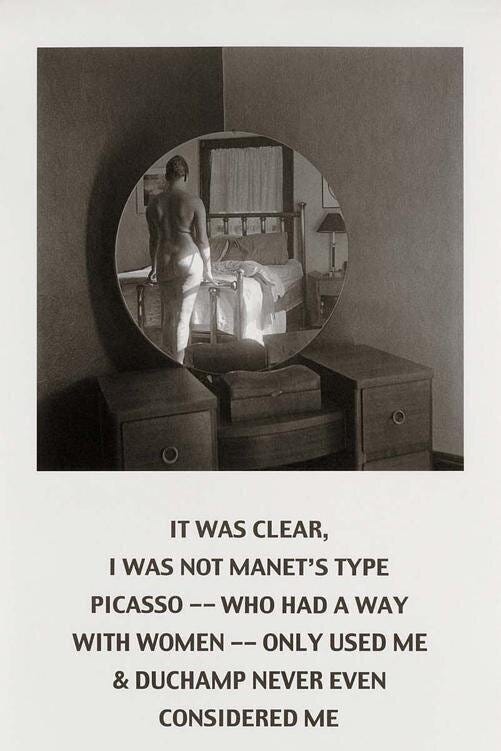

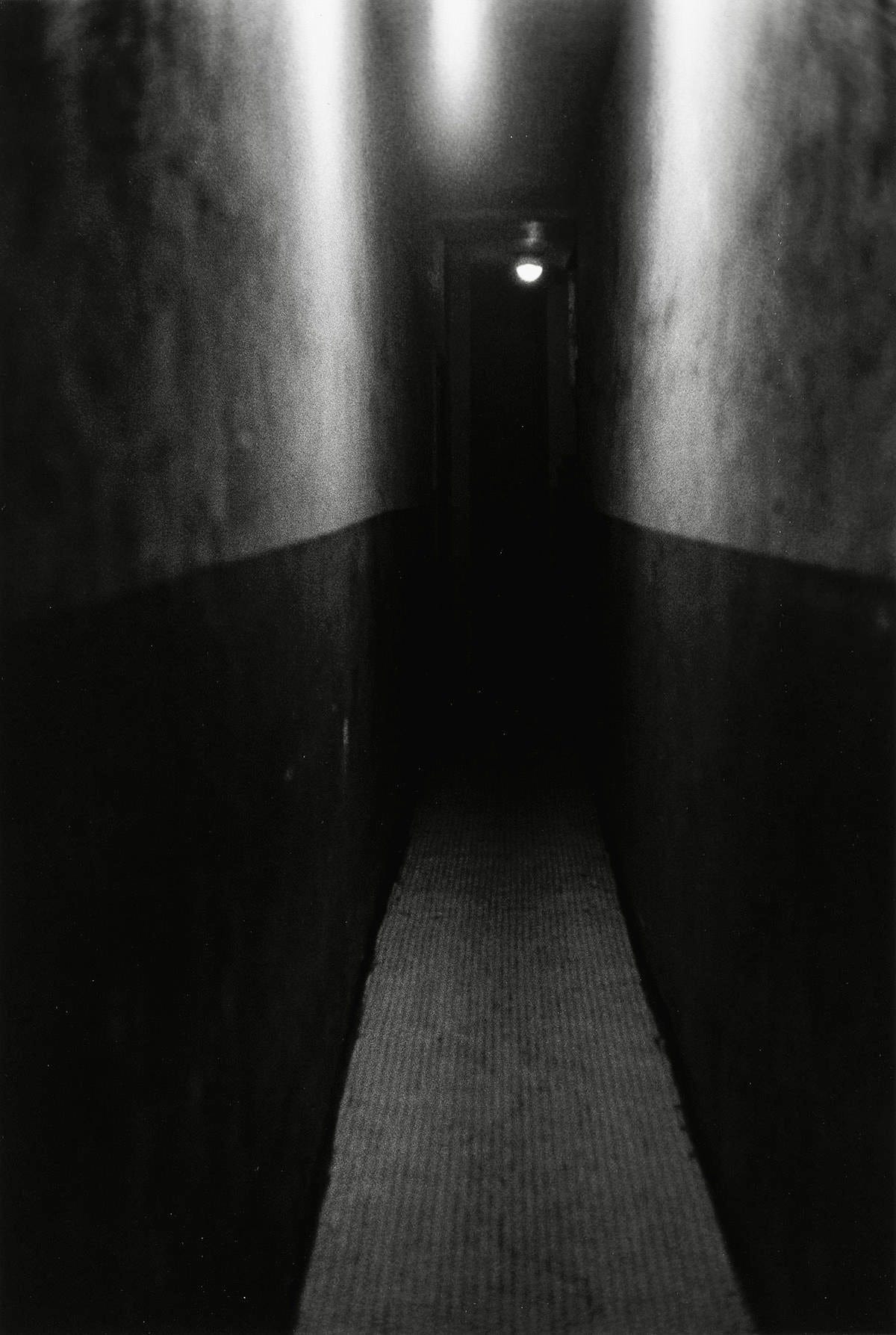

There’s a quote about beauty from photographer Roy DeCarava that I love and have hung up on a wall:

If I ever wanted to be marooned with one photograph, I think I would want to be marooned with “Hallway” simply because it was one of my first photographs to break through a kind of literalness. It didn’t break through, actually, because the literalness is still there, but I found something else that is very strong and I linked it up with a certain psychological aspect of my own. It’s something that I had experienced and is, in a way, personal, autobiographical. It’s about a hallway that I know I must have experienced as a child. Not just one hallway; it was all the hallways that I grew up in. They were poor, poor tenements, badly lit, narrow and confining; hallways that had something to do with the economics of building for poor people. When I saw this particular hallway I went home on the subway and got my camera and tripod, which I rarely use. The ambience, the light in this hallway was so personal, so individual, that any other kind of light would not have worked. It just brought back all those things that I had experienced as a child in those hallways. It was frightening, it was scary, it was spooky, as we would say when we were kids. And it was depressing. And yet, here I am an adult, years and ages and ages later, looking at the same hallway and finding it beautiful […] You can profit from a negative and make it positive. As beautiful as the photograph is, the subject is not beautiful in the sense of living in it. But beauty is in being alive—strange that I should use that word living! But it is alive.

This week’s encounters:

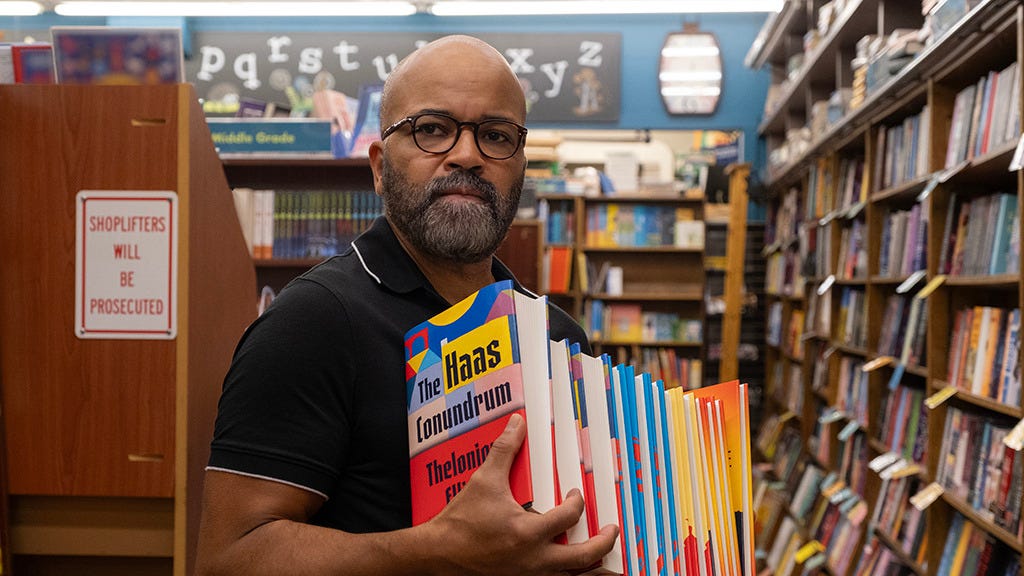

I. A film - American Fiction

This week I saw American Fiction, Cord Jefferson’s feature directorial debut. I thoroughly enjoyed it and found myself surprised—and impressed—by the film’s dramatic and emotional range. Based on Percival Everrett’s novel Erasure, American Fiction follows Thelonious “Monk” Ellison (played by Jeffrey Wright), a frustrated novelist and professor living in Los Angeles. Fed up with the publishing industry’s predilection for stereotypical stories about Black representation, Monk decides to try his hand at writing one of them under a pen name, a novel titled My Pafology. My Pafology is rife with stereotypes: a deadbeat dad, gun violence. To Monk it’s all a joke, yet the industry eats it up. I went into the film expecting a fairly straight satire and was met with a wonderfully complex and layered narrative. It was refreshing, smart, truly funny, and moving. What else can one ask for in a film?

American Fiction also made me consider my own relationship to “the problem of representation.” It’s a question that goes all the way back to DuBois’s concept of double-consciousness, found in his essential The Souls of Black Folk (1903). It’s a concept so repeated that it almost seems too obvious to mention. But when you read DuBois in Souls, the phrase deepens. One feels the force of that fundamental alienation as a loss of innocence; he describes the experience as a “vast veil.” It is a loss that is completely metaphysical, one that upends one’s relationship to language and the self.

While watching American Fiction, I was reminded of James Baldwin’s “Autobiographical Notes” from his collection of essays Notes of a Native Son. I’ve been re-reading Baldwin and remembering how foundational his ideas have been to my development as a writer. He really set the path for so many of us who have felt constrained by the pressure to only write about our race or identity. I read him and am always reminded of my humanity:

One writes out of one thing only—one’s own experience. Everything depends on how relentlessly one forces from this experience the last drop, sweet or bitter, it can possibly give. This is the only real concern of the artist, to recreate out of the disorder of life that order which is art. The difficulty then, for me, of being a Negro writer was the fact that I was, in effect, prohibited from examining my own experience too closely by the tremendous demands and the very real dangers of my social situation […] I have not written about being a Negro at such length because I expect that to be my only subject, but only because it was the gate I had to unlock before I could hope to write about anything else.

Whether it’s the veil or the gate, it is something that must be passed through.

American Fiction was also a one of the most interesting movie-going experiences I’ve had all year. I went with a friend, who also isn’t white. To our left sat a white couple, the woman directly next to me. My friend and I both noticed how the white woman would laugh loudly at all the expected moments—even looking over at us from time to time—but stayed silent whenever my friend and I would laugh. It seemed like the jokes that cut deeper didn’t register. Or perhaps they were a little too close to home.

II. An album - The Omnichord Real Book

This week I listened to “An Elastic and Impressive Moment in Jazz” on the NYT Popcast, hosted by journalist and critic Jon Caramanica. I’ve been listening to Popcast for years; although I used to host a radio show in college, I now feel woefully behind on what’s exciting and new in music.

I love jazz, something I inherited from my father. When all else fails, it’s often the music I turn to. I was delighted to discover Meshell Ndegocello’s latest album The Omnichord Real Book, which was released this past summer. I’ve been in a real listening rut and finding this album has been a highlight of my week.

III. Flora - Rafflesia arnoldii

This week I discovered the existence of Rafflesia, a genus of parasitic flowering plant found in Southeast Asia, and am now obsessed. Rafflesia is known for producing the largest individual flower found on Earth, Rafflesia arnoldii, also known as the “stinking corpse lily.” Like the titan arum, it is known for its incredibly repulsive smell. I saw the titan arum in person at The Huntington in Pasadena this summer, and I’d love to see a rafflesia variety one day!

As always, thank you for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please don’t hesitate to share it. These weekly posts are free, and every single view and subscription directly supports me and my work.

I’ll see you in a week 💌